Since mid-March 2022, Defra has persisted with its claims regarding an independent scientific paper (1) that extensively analysed government data on herd bTB incidence and prevalence in the High Risk Area of England since 2010. The paper compares areas subject to badger culling with those that were not culled in each year of the controversial mass badger culls from 2013-2019.The paper concludes that badger culling has had no measurable benefit in bovine TB disease reduction, and Defra continue to claim that the paper is flawed.

Defra’s and Natural England’s position on this new analysis, including apparently that of the Defra chief scientist (CSA), Gideon Henderson and chief vet (CVO) Christine Middlemiss, seems to be based on their dislike of the statistical approach of the new paper, which differs from Defra’s traditional approach to badger cull evaluation.

Defra/APHA prefer to try to mimic the analytical methods of the Randomised Badger Culling Trial (RBCT). They take cull areas and compare them with different unculled areas, adjusting the data considerably to try to take account of the subtle or sometimes profound differences between compared areas. The new study took a different approach. This study looked at the same (or 97% of) herds over the years of study, so spatial differences were minimized. The analysis used data from herds when they were in unculled areas, and then again when they were in culled areas following their transition from one to the other. This simple approach, dictated by Defra secrecy over cull area locations, brings different strengths and requires less interference with the data. The approach enabled all the data available to be used, not just selected parts of it that might lead to skewed, inaccurate results and conclusions. Just look, for example, at the tangled caveats in the Downs paper from 2019 of just three culled areas and multiple unculled areas.

But Defra are very bold in their criticism : “the analysis was scientifically flawed. It manipulated data in a way that makes it impossible to see the actual effects of badger culling and therefore its conclusions are wrong.” Confident claims, but do they have merit?

Defra’s ‘inappropriate grouping’ claim

Defra’s main objection surrounds the issue of what they call ‘inappropriate grouping’ of data. This is the key point in the letter that they pressed the Veterinary Record journal to publish alongside the shortened printed version of the paper on 18th March. This was reported on in more detail here.

The problem in Defra’s claim goes beyond the calculation mistakes in their 18 March Vet Record graph, that they subsequently (in May) apologised for, retracted & replaced with results more similar to those in the new paper. Defra’s presented data shows the herd bTB incidence reducing dramatically in the first and second years from cull commencement. This is the same data as used in the new paper, so this is no surprise. But the point is, Defra say that you cannot group data from years one and two of culling with that from the third and later years because the level of decline in years one and two are too small, and this will remove all signs of effect. However, the Defra graphs do not show that the level of decline in years one and two in cull areas is small, and this is the contradiction that they refuse to talk about.

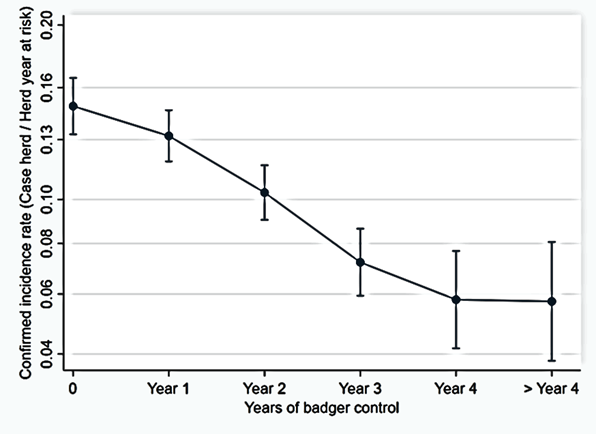

Similarly, the analysis presented by APHA staffer Colin Birch at the IVSEE16 conference in Nova Scotia, Canada earlier this month, (2) Figure 1, does not show that the level of decline in years one and two is small either. It showed sustained decline over 4 years, with a similar level of decline each year right from the start. Yet it provided no comparison of data from the 25% of the HRA that remains unculled. To the audience’s complaint, here, he quite wrongly tried to attribute these declines to badger culling.

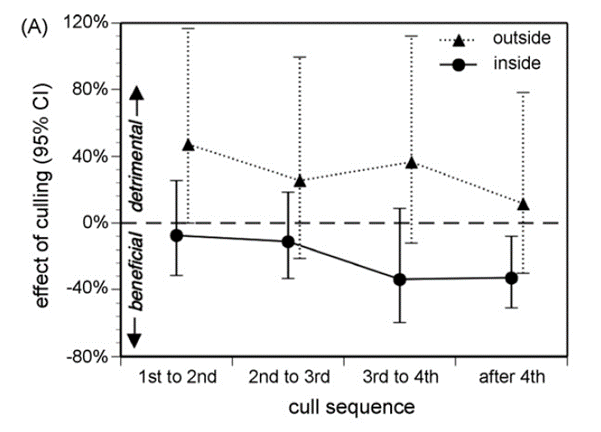

So where did the ‘inappropriate grouping’ comment come from? Well, it is likely that Defra have fallen back on RBCT advice and the 2006 and 2007 (3,4) papers that presented the findings of 10 treatment-control area comparisons of small cull areas. These papers showed large variation in the estimated levels of decline in bTB herd incidence in culling areas, so much so that the confidence intervals (CI) on the presented graph figure 2A (Figure 2.) passed through 0 in most years.

Estimated average declines were 3.5% in year 1 and 12.8 % in year 2, with 39% in year 3. So, you can see that by using the RBCT as a prior reference source (this the point of reference used in Defra/APHA documents), there could be an expectation that there isn’t much disease reduction in years 1 and 2. However, while the drop may not have been projected to show significance until year 3, the decline trend should be present and visible by the end of year 2.

So looking again at Figure 1 (Birch 2022 abstract), government is now turning this on its head and claiming, in contradiction, that bTB incidence among cattle herds reduced by around 15% per year in each of the first two years of badger culling.

Defra’s unsupported point was also made by Cambridge vet James Wood on Radio 4 Farming Today on 19th March 2022, but it simply doesn’t stack up. Even if there was just a modest (say 8% average) annual benefit in years 1 and 2, it would still have shown up in the new paper analysis in comparison with unculled areas when using such a huge amount of data, as is possible using the 2016 onwards rolled-out HRA badger culls.

Ridiculously, Defra have previously claimed substantial benefit in years 1 and 2 from the post-2013 cull data, and used this as a basis for claiming badger culling was working. They did this spectacularly in 2017 with the APHA Brunton et al. paper (5) that suggested benefit 32% in Somerset, and 58% benefit in Gloucestershire in the first two years, and again in 2019 with the notorious and heavily caveated Downs et al. paper using data to-2017 (6), that was undone by the 2018 results (7), also published in the veterinary literature, with slightly more claimed benefit (Table 1 below).

|

Pilot cull Area 2013-2017 |

Brunton et al. 2017 |

Downs et al. 2019 |

Percent est. in Yrs 1 and 2 |

|

Gloucestershire 1 |

58% |

66% |

88% |

|

Somerset 1 |

32% |

37% |

86% |

Table 1. Claimed benefit from badger culling in Brunton et al (5) and Downs et al (6).

The Defra Minister and MP’s were told that badger culling was working based on this claimed year 1 and 2 benefit. They told parliament and the public in no uncertain terms that badger culling was working, so they can’t really go back on it now without losing face. James Wood also told Countryfile views that he thought the data showed badger culling was working based on the first two-years of pilot data. So, who is talking in riddles now?

The problem that Defra have, and it is why they have clammed up to the scientists and media, is that if Defra/the CSA/CVO were to communicate beyond the bold claims made in March in Vet Record and on the Defra media blog, they would lose the argument. Defra have written to the first author saying they are not prepared to discuss the matter. Caught, it seems, between their scientific advisors’ comments, legal undertakings to monitor efficacy and policy-mania to keep on badger culling in the face of failure. Even Natural England have gone as far as saying that the situation is unclear “Because these different control measures are being implemented simultaneously, it is difficult to determine the relative contribution each of them is making to disease reduction.”

Insufficient data points?

One argument Government have used to dismiss the validity of the new paper is that it has insufficient data points. While the new study does has few data points, each data point summarises a huge amount of data representing hundreds or thousands of herds, helping to obviate the kind of problems caused by the smaller data sets of APHA studies. The approach is equally or more valid. It did, after all, pass rigorous peer-review (4 reviewers including at least two epidemiological statistical specialists) in a leading veterinary journal.

Basically, Defra lost both arguments, rebutting the paper in short measure, and it is astonishing that CSA Henderson CVO Middlemiss were given this position to hold, let alone to defend. No wonder Middlemiss got muddled on Farming Today over it on 25 May. This problem is now many months old and Defra and Natural England have carried their unsubstantiated criticisms along to justify the licensing of further supplementary culling licences in May and intensive culling licenses from August. This means the killing of tens of thousands more largely healthy badgers over the next four years to add to the roughly 200,000 that have been slaughtered to date. This flies in the face of peer-reviewed science, against which Defra have failed to produce anything credible or comprehensive that is peer-reviewed.

At the Birdfair State of the Earth panel debate on 15th July of this year, the retired badger cull architect Prof Ian Boyd: Chief Scientific Adviser at Defra (2012-2019) commented: “Well, if badger culling isn’t working it shouldn’t be done, that’s absolutely clear. I think there is still an ‘if’ there, but I suspect that the evidence is suggesting it doesn’t work.”

And Prof David Macdonald at Oxford, who chaired the Natural England Scientific Advisory Committee for many years, and who called the Pilot culls an ‘epic fail’ has commented in Chapter 16 of his new Oxford University Press book ‘The Badgers of Wytham Woods’: “ it is hard to see how Middlemiss and Henderson land a knock-out punch on Langton et al’s analysis..”

There is nothing very dramatic or complicated here in Defra’s last stand. Defra has lost the scientific argument. They must surely now face abandoning the failed badger culling policy altogether. They really should talk openly about it.

References

1. Langton TES, Jones MW, McGill I. Analysis of the impact of badger culling on bovine tuberculosis in cattle in the high-risk area of England, 2009–2020. Vet Rec 2022; doi:10.1002/vetr.1384.

2. Birch, C. Prosser, A. and Downs S. An analysis of the impact of badger control on bovine tuberculosis in England. Abstract oral presentation to ISVEE16, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. 2022.

3. Donnelly, C. A. et al. Positive and negative effects of widespread badger culling on tuberculosis in cattle. Nature 439, 843–846 (2006).

4. Donnelly CA, Wei G, Johnston WT, Cox DR, Woodroffe R, Bourne FJ, Cheeseman CL, Clifton-Hadley RS, Gettinby G, Gilks P, Jenkins HE, Le Fevre AM, McInerney JP, Morrison WI. Impacts of widespread badger culling on cattle tuberculosis: concluding analyses from a large-scale field trial. Int J Infect Dis. 2007 Jul;11(4):300-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2007.04.001. Epub 2007 Jun 12. PMID: 17566777.

5. Brunton LA, et al. Assessing the effects of the first 2 years of industry-led badger culling in England on the incidence of bovine tuberculosis in cattle in 2013–2015. Ecol Evol. 2017;7:7213–7230. doi: 10.1002/ece3.3254. – DOI – PMC – PubMed.

6. Downs S H, Prosser A, Ashton A, Ashfield S, Brunton L A, Brouwer A, et al. Assessing effects from four years of industry-led badger culling in England on the incidence of bovine tuberculosis in cattle, 2013–2017. 2019. Sci Rep. 2019; 9:14666.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49957-6. Accessed 16 June 2021

7. Mcgill I, Jones M. Cattle infectivity is driving the bTB epidemic. Vet Record. 2019; 185(22), 699 – 700.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31806839/.

Discover more from The Badger Crowd - standing up for badgers

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.