The original Randomised Badger Culling Trial (RBCT) analysis

The Government’s English badger cull policy since 2011 has rested all but entirely on the RBCT analyses, the first of which was Donnelly et al (2006). It is the science that DEFRA has used to create intensive, supplementary and Low Risk Area (LRA) policy and in court to defend their decisions to ‘experiment’ with badger culling. The claim from this work was that badger culling along similar lines can reduce bovine TB cattle herd breakdowns by around 16% per year; dozens of subsequent studies used in policy and to inform economic and operational models on which the badger cull policy hangs, were heavily derived from and dependent on the RBCT and most of these remain in place in 2025.

A challenge to the RBCT analysis First preprinted in December 2022, a comprehensive re-evaluation of the RBCT was published in July 2024 in Nature Scientific Reports (Torgerson et al 2024). The new study re-examined data from the RBCT proactive culling experiment, using the most epidemiologically appropriate range of statistical models, in accordance with the experiments design. It concluded that most standard analytical options show no evidence to support an effect of badger culling on bovine TB in cattle. The statistical model selected for use in the original study in 2006 was one of the few models that did show an effect from badger culling. However, various criteria suggest that the original model was not an optimal model compared to other analytical options then available; the most likely explanation for the claimed culling benefit was that the chosen model ‘overfitted’ the data and used a non-standard method to control for disease exposure. This gave the model a poor predictive value, i.e. it was not useful in predicting the results of badger culling. The more appropriate models in the Torgerson study strongly suggest that badger culling did not bring about the disease reduction reported. Further, inclusion of ‘all reactors’ to the tuberculin test showed no effect of culling irrespective of the model used.

First preprinted in December 2022, a comprehensive re-evaluation of the RBCT was published in July 2024 in Nature Scientific Reports (Torgerson et al 2024). The new study re-examined data from the RBCT proactive culling experiment, using the most epidemiologically appropriate range of statistical models, in accordance with the experiments design. It concluded that most standard analytical options show no evidence to support an effect of badger culling on bovine TB in cattle. The statistical model selected for use in the original study in 2006 was one of the few models that did show an effect from badger culling. However, various criteria suggest that the original model was not an optimal model compared to other analytical options then available; the most likely explanation for the claimed culling benefit was that the chosen model ‘overfitted’ the data and used a non-standard method to control for disease exposure. This gave the model a poor predictive value, i.e. it was not useful in predicting the results of badger culling. The more appropriate models in the Torgerson study strongly suggest that badger culling did not bring about the disease reduction reported. Further, inclusion of ‘all reactors’ to the tuberculin test showed no effect of culling irrespective of the model used.

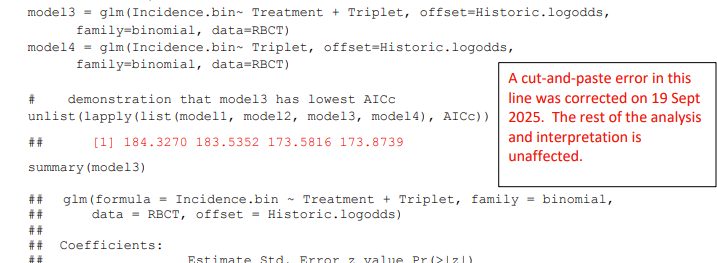

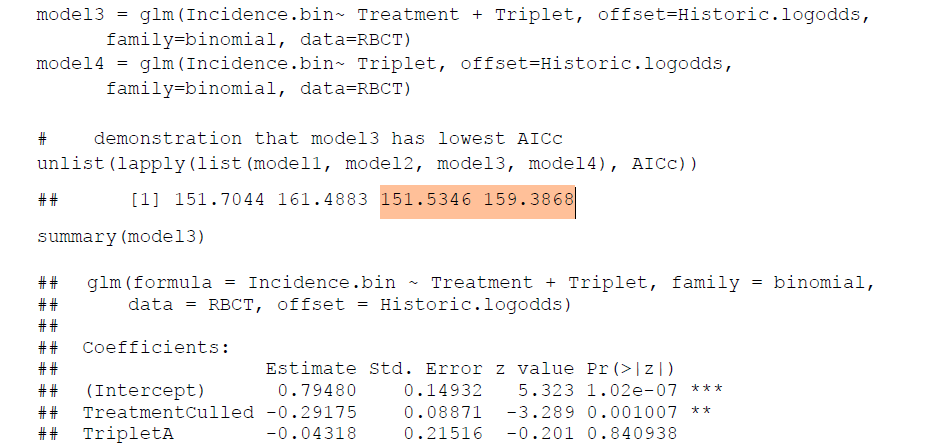

Shortly after, on 21st August 2024, and as a response to Torgerson et al 2024, two of the authors of the original analysis of the RBCT from 2006 (together with a third student author) published two new papers in the Royal Society Open Science journal (Mills et al 2024a&b) using large amounts of the Torgerson preprinted models and doubling down on their original conclusions saying they were ‘robust’. On 16th September 2024, a ‘Comment’ response to the new Mills et al. 2024 papers was submitted to the RSOS: “Randomised Badger Culling Trial—no effects of widespread badger culling on tuberculosis in cattle: comment on Mills, Woodroffe and Donnelly (2024a, 2024b), (Torgerson et al 2025). After a delay of eight months, this was accepted (with minor modifications) on April 23rd 2025 and published on 11 June. This new publication further exposed the flaws of the original RBCT analyses and the more recent attempt to defend it (Donnelly et al 2006 and Mills et al 2024a&b). The findings were endorsed by a senior biostatistician who described key aspects of analytical choices in Mills et al. and the 2006 paper as “naive at best” (Brewer 2025). A letter in Vet Record from October (Torgerson 2025) states that “A request has been sent to retract the 2006 RBCT proactive culling paper, as the results have been shown to be untenable. In my view papers published since 2006 that are reliant on the veracity of the RBCT analysis and results also need to be corrected or retracted.“

The latest Godfray review update of the science of bovine TB (Godfray et al 2025) published in September 2025 agreed that the Torgerson et al. 2024 analysis is the more ’natural’ way to analyse the RBCT data, but beyond its brief to review scientific material published since 2018, decided to undertake its own analysis. This used a binomial rather than Poisson approach to conclude a badger culling benefit from the RBCT data, but at a much lower level of significance than previously presented – it was transformed from ‘weak’ not ‘strong’. Thus agreeing with Torgerson and destroying evidence for the perturbation effect hypothesis.

However, the Godfray/Silverman RBCT model in the review update has additional flaws, and it is not based on the complete data set; it did not include the important ‘time at risk’ variable. As a result, its binomial model follows a similar pathway as the 2006 analysis. When time at risk is included with the appropriate adjustments, the results suggest no effect of culling. In reality the Godfray/Silverman work pulls down the Donnelly 2006 analysis and then itself, completely undermining the RBCT and a vast volume of subsequent science and policy based upon it. A preprint outlining the various problems with the new model was posted in October 2025 (Torgerson 2025).

Godfray’s review update concluded that the RBCT now provides “limited (if any) insights into the design and likely value of including culling in a control programme”, despite the basis and inference it provides for a large number of later studies, including whole genome sequencing (WGS), which it now looks to for “valuable new information about the risk of infection from badgers”. The huge importance of the loss of Donnelly et al (2006) and its associated papers as plausible science is not mentioned.

APHA analysis of the industry-led badger culls

Brunton et al (2017) and Downs et al (2019) analysed data from the first two, and then up to four years of culling respectively, but for only 2 and 3 cull areas respectively. Large benefits from culling were claimed, but neither had sufficient data to draw robust conclusions and both were heavily caveated. Both repeated the statistical flaws of the Donnelly et al. 2006 analysis and Donnelly was a co-author. These papers too are now invalidated by the recent appraisals.

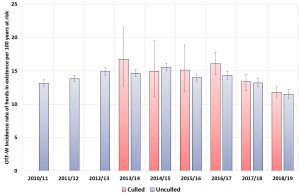

In March 2022, a new study (Langton et al 2022) in Veterinary Record journal, looked at data from the first six years of badger culling. Firstly, it looked at herd breakdown incidence and prevalence of cattle bTB in areas that had undergone a badger cull and compared them with the data from areas that had not had culling. This was done over a seven-year period 2013-2019, so before and after culling was rolled out in 2016; hence it was a study of the first three years of culling. Multiple statistical models checked the data on herd breakdowns over time and failed to find any association between badger culling and either the rate of incidence or prevalence of bovine TB in cattle herds.

In March 2022, a new study (Langton et al 2022) in Veterinary Record journal, looked at data from the first six years of badger culling. Firstly, it looked at herd breakdown incidence and prevalence of cattle bTB in areas that had undergone a badger cull and compared them with the data from areas that had not had culling. This was done over a seven-year period 2013-2019, so before and after culling was rolled out in 2016; hence it was a study of the first three years of culling. Multiple statistical models checked the data on herd breakdowns over time and failed to find any association between badger culling and either the rate of incidence or prevalence of bovine TB in cattle herds.

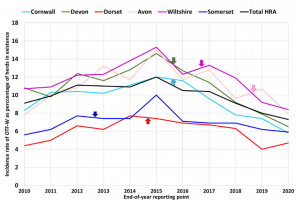

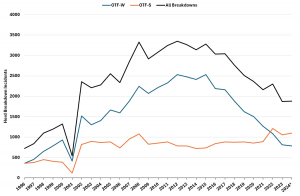

Secondly, the 2022 paper looked at the trends over time of disease rates for the same period. Data suggests that the cattle-based testing and movement control measures, including annual tuberculin testing from 2010, were most likely responsible for the slowing, levelling, peaking and decrease in bovine TB in cattle in the High Risk Area (HRA) of England during the study period, in most areas well before badger culling was rolled out.

Secondly, the 2022 paper looked at the trends over time of disease rates for the same period. Data suggests that the cattle-based testing and movement control measures, including annual tuberculin testing from 2010, were most likely responsible for the slowing, levelling, peaking and decrease in bovine TB in cattle in the High Risk Area (HRA) of England during the study period, in most areas well before badger culling was rolled out.

Despite being rigorously peer-reviewed (by 4 peer-reviewers, including Vet Records in-house statistician), the paper and its authors were attacked by Defra in the media and on their blog, and its findings were not accepted. The Chief Veterinary Officer and Defra’s Chief Scientific Advisor published a rebuttal letter alongside Langton et al, claiming their data showed that badger culling was working. Six weeks later Defra admitted that their data was wrong and published a new graph of data. They maintained, however, that this did not change their overall conclusions about the new paper, and did not respond to the rebuttal arguments that the authors put forward in the 2nd April 2022 issue of the journal Veterinary Record. Criticisms by government suggested that greater declines had happened in culled areas, but the confidence intervals were too large to show any clear effect. No analysis was offered by Defra to back up the claim who attacked the papers authors, the peer reviewers and the journal. Subsequent ‘Freedom of Information’ requests released emails showing that Defra had sought to block the paper after it had been accepted.

No further comment was made from Defra until (at the Request of Godfray/Silverman) the posting of a preprint, Robertson (2025), that used the disputed analyses (from Donnelly 2006 & Birch 2024 see below) to generate data simulations, to claim that Langton et al may not have detected a disease benefit if one had existed. This used a lower estimated change of 2.8% reported in the first years of culling by RBCT model outputs, rather than the substantial claimed benefits in the more recent APHA papers. The arguments put forward by Robertson are addressed in a brief preprint by Langton (2025) demonstrating that a normal approach to checking data variation shows the Robertson claims are highly likely to be spurious.

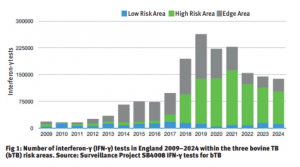

The February 2024 paper by Defra staff (Birch et al.) was used to justify further culling proposals in the March 2024 Defra ‘targeted culling’ consultation, and implied, using convoluted wording and without any evidence, that the culling programme thus far had been successful. This was repeated heavily by the Minister and trade press, creating a mass mis-information process that was countered by the incoming Labour government that called culling ‘ineffective’. Authors of Birch twice acknowledge (on careful reading) that while they may speculate, the overall changes in disease levels cannot be attributed to badger culling: all disease measures implemented, including new additional and extensive testing, were analysed together with no control. Claims of badger cull benefit from this analysis are further undermined by its under-declaration of the use of Gamma interferon testing; Birch claims this wasn’t being carried out during the first two years of culling, but government data suggests otherwise (see here and here). There was no comparison of culled and unculled areas, despite the Godfray review update suggesting that there was. Birch cannot attribute recorded benefit to badger culling and provides no insight at all.

Writing in a preamble to Badger Trust’s report ‘Tackling Bovine TB Together’, key badger ecologist and original RBCT scientist Professor David Macdonald writes that the authors of Birch “… do not claim to have measured the consequences of badger culling, and indeed they have not”, and, “there is still no clearcut answer regarding the impact of this approach to badger culling on controlling bTB in cattle or, more broadly, whether it’s worth it.”

A flawed method to identify the source of infection

Badger culls have previously been justified using the guess-based ‘Risk Pathways’ approach of the Animal Plant and Health Agency (APHA). This system sees farm vets invited to speculate on the likely origin of infection. If they are unable to link it to a previous cattle infection (they only look back four years), they often tick the box that blames an environmental source, by default badgers. No evidence is required. However, a study in TB-Free Switzerland of a single-source new outbreak found suggested persistence of bovine TB in a dairy herd for nearly fifteen years without detection (Ghielmetti et al 2017). Further, it is now accepted that the standard SICCT test, at standard interpretation, has an average herd sensitivity of around 50%, thus missing up to half of infected herds and several infected animals per herd; hence disease is remaining undetected in around 20% of herds. The lack of scientific evidence supporting the APHA approach in the Low Risk Areas to identifying the source of disease is discussed in the independent report Griffiths et al (2023).

A new way to blame badgers – Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS)

The Godfray review update (2025) strongly endorses the use of WGS, saying; “…recently introduced techniques, especially WGS, have provided valuable new information about the risk of infection from badgers, consistent with, but significantly extending, the original inference from the RBCT that badgers do present some risk to cattle”.

However, this is a broad and unqualified statement . While WGS studies (there are around nineteen of them) generally report some evidence that a particular strain has been found, time-dated, in a sampled badger and a sampled cow, they do not accurately report the frequency with which transmission occurred, nor the exact route, which may even be via another organism. WGS’s capacity to deliver conclusive findings in the exact route of transfer of pathogens between hosts is still in its infancy and constrained by accuracy in controlling and sampling multi-host situations in varied commercial settings over relatively long periods of space and time. Outcomes are dependent on choices made within complex models that are often not published, are speculative and should be considered with utmost caution. The results reported by WGS studies are not consistent; conclusions reported differ widely. The Godfray review update listed some of the findings but did not do any critical evaluation of them; this remains absent. There is a risk that the Godfray review may repeat the same failings as the Godfray restatement of RBCT findings in 2013, published by the Royal Society, by not checking the veracity of publications.

Some of the WGS studies have used results from the original RBCT analyses in their modelling, which subsequent to successful challenge, should now be seen as scientifically unsupported. Many use the RBCT’s inference of the supposed benefit of badger culling as inference of a likely transmission route from badger to cow and likewise are now unsound.

Are ‘unconfirmed’ reactors infected with bovine TB?

The Godfray review in 2025 was charged with ruling on the matter of whether cattle which react to a lesser extent to the SICCT test, but where they pass subsequent tests should be categorised as infected. This distinction is of great significance because when ‘all’ data (confirmed and unconfirmed) are included in the RBCT analyses, no badger culling benefit is found (in Donnelly et al 2006 or Torgerson et al 2024). Also, because until recently, stock known to be infected (Officially Btb-Free Suspended (OTF-S)) could be kept in the herd and traded in England.

Importantly, APHA epidemiological monitoring of bTB incidence currently focusses on confirmed reactor data (Officially BTB-Free Withdrawn (OTFW)) to report on the progress of disease control. Inclusion of unconfirmed animals in the data (prevalence) indicates that the disease remains largely unchanged after 12 years of Badger Control Policy (BCP) (Langton and Torgerson 2025). An explainer for the jargon around this issue is available here.

Importantly, APHA epidemiological monitoring of bTB incidence currently focusses on confirmed reactor data (Officially BTB-Free Withdrawn (OTFW)) to report on the progress of disease control. Inclusion of unconfirmed animals in the data (prevalence) indicates that the disease remains largely unchanged after 12 years of Badger Control Policy (BCP) (Langton and Torgerson 2025). An explainer for the jargon around this issue is available here.

The Godfray update did not determine this issue however, saying only; “Detailed research is needed to allow these questions to be addressed systematically in ways that achieve a consensus among the various stakeholders.

Policy implications for badger culling are considered here.

The Westminster Hall debate of the Protect the Wild petition, held on 13th October, was a significant improvement on previous badger cull debates. The majority of voices spoke earnestly about a wish to stop badger culling and address TB testing failures as soon as possible. There wasn’t a repeat of the nonsense we have previously seen; “too many badgers” and “killing hedgehogs, bees and ground nesting birds”. And the Minister Angela Eagle concluded by committing to ending the badger cull by the end of this Parliament (2029), possibly hinting at terminating remaining licenses to bring all culling to a conclusion in 2026.

The Westminster Hall debate of the Protect the Wild petition, held on 13th October, was a significant improvement on previous badger cull debates. The majority of voices spoke earnestly about a wish to stop badger culling and address TB testing failures as soon as possible. There wasn’t a repeat of the nonsense we have previously seen; “too many badgers” and “killing hedgehogs, bees and ground nesting birds”. And the Minister Angela Eagle concluded by committing to ending the badger cull by the end of this Parliament (2029), possibly hinting at terminating remaining licenses to bring all culling to a conclusion in 2026.

Writing in a preamble to Badger Trust’s report ‘Tackling Bovine TB Together’, key badger ecologist and original

Writing in a preamble to Badger Trust’s report ‘Tackling Bovine TB Together’, key badger ecologist and original  Badger culls have previously been justified using the guess-based ‘Risk Pathways’ approach of the Animal Plant and Health Agency (APHA) that purported to explain how disease arrives in a herd. Its ‘tick-based’ veterinary questionnaires implicated badgers as the default primary source of disease when adequate epidemiological information and investigation was lacking. Following publication of the report ‘

Badger culls have previously been justified using the guess-based ‘Risk Pathways’ approach of the Animal Plant and Health Agency (APHA) that purported to explain how disease arrives in a herd. Its ‘tick-based’ veterinary questionnaires implicated badgers as the default primary source of disease when adequate epidemiological information and investigation was lacking. Following publication of the report ‘ Langton et al. 2022, was done in the most logical and clear-cut way using all the data. It shows what happens as unculled areas become culled, from 2013 onwards. The paper has two main findings. The first is really good news for farmers, cows and badgers. Data suggests that the cattle-based measures implemented from 2010, and particularly the introduction of the annual tuberculin skin (SICCT) test are responsible for the slowing, levelling, peaking and decrease in bovine TB in cattle in the High Risk Area (HRA) of England during the study period, all well before badger culling was rolled out in 2016.

Langton et al. 2022, was done in the most logical and clear-cut way using all the data. It shows what happens as unculled areas become culled, from 2013 onwards. The paper has two main findings. The first is really good news for farmers, cows and badgers. Data suggests that the cattle-based measures implemented from 2010, and particularly the introduction of the annual tuberculin skin (SICCT) test are responsible for the slowing, levelling, peaking and decrease in bovine TB in cattle in the High Risk Area (HRA) of England during the study period, all well before badger culling was rolled out in 2016. Commenting on this work,

Commenting on this work,

Back in the day, and well before their ‘not-so-sensible after all’ 2001 merger with the Department of Environment, Transport and the Regions (DETR), the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, (MAFF), were influential in deciding what government should do about badgers.

Back in the day, and well before their ‘not-so-sensible after all’ 2001 merger with the Department of Environment, Transport and the Regions (DETR), the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, (MAFF), were influential in deciding what government should do about badgers.

A paper entitled “The activism responsibility of climate scientists and the value of science-based activism” (

A paper entitled “The activism responsibility of climate scientists and the value of science-based activism” (