There’s no evidence that it can work….

There are many government reports and a growing number of academic papers investigating the potential use of badger vaccination to attempt control over bovine TB infections in cattle. They mostly start from an outdated government premise that badgers are somehow a maintenance host, responsible for half or more of herd breakdowns. Scientifically there is acceptance of the lack of evidence for efficacy of badger vaccination as a method to reduce bovine TB incidents in cattle herds. There is just an assumption that if they were involved, reducing levels in badgers might aid bTB control.

Badger vaccination can be expected to reduce bTB in badgers, but………

Published analysis has for decades shown that, as expected, vaccinating badgers can reduce the prevalence of bTB in them (Aznar et al 2018, Benton et al 2020, Robertson et al 2025, Smith et al 2022). But without reliable information on how this relates to cattle bTB breakdowns, the huge cost of a highly intrusive wildlife intervention may be just another pointless waste and distraction to addressing the very well established and overdue shortfall in cattle testing and movement control – the problem that perpetuates the epidemic.

The government field trial ‘Vaccinating East Sussex Badgers’ (VESBA) scheme in Sussex study is coordinated by a commercial veterinary group. It has organised a badger vaccination project within a 250 km2 area, (see in APHA’s Year End Descriptive Epidemiology Report of Bovine TB in the Edge Area of England 2024, East Sussex). Latest reporting suggests that badger vaccination may reduce the prevalence of bTB in cattle, feeding the government narrative. But its a guess.

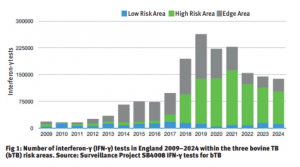

The messaging outputs from such studies, as with those from badger culling, are often not scientifically rigorous. They tend to originate from anecdotal comments by those involved expressing belief that some good is being done. In this case, because breakdowns reduced from 15 to 1 during a period from 2018. But this is the same period that the study area was subject to heavy Gamma interferon testing. The effects of vaccination are not separable from the enhanced cattle measures used in Sussex – principally Gamma testing – that are being implemented simultaneously. This was the approach used by APHA to claim benefits from badger culling since 2013 in the ‘High Risk’, ‘Edge’ and ‘Low Risk’ areas, brought out like an old party trick to try to claim success, where none could be quantitatively shown.

Is the ‘placebo’ effect of telling farmers and vets that vaccination is (or is likely to) benefit cattle, the key to getting them to accept enhanced testing with its greater loss of stock to premature slaughter? This appears the philosophy behind badger vaccination (and culling previously). Even if such an approach is ethical, it cannot work due to the number of infections often left in the herd, even after gamma testing.

If badger culling has had no measurable impact on btb in cattle, neither will badger vaccination?

For badger vaccination to effect cattle herd breakdowns, badgers would need to be transmitting bTB to cattle in pastures at a relatively high frequency, and this has never been demonstrated. Nor has any plausible, evidenced transmission route been shown – the key element of basic epidemiology. Badger culling has also not been shown to have a measurable effect on rate of bTB herd breakdown. (See summary of the science here).

More recently, reference has been made to Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) papers to make claims of transmission rates between and within cattle and badgers.

Study of the APHA epidemiology reports for each county illustrates how WGS use for tracing in breakdown investigations cannot show badger to cattle transmission. For investigations, WGS is only applied to identify clades. This is just a slight improvement on looking at spoligotypes. In practice, WGS for disease control leaves large uncertainty as to the source of tb in cattle, attributing badger as the default. If WGS was applied at finer resolution, and sufficient isolates were available, the data could clearly and unequivocally trace the source of disease back to the index case, at the individual level and in real time. But that isn’t being done.

The current disease report system does not take into account the incorrect assumptions made in APHA’s interpretation of WGS information. Every week, this leads to herds reinfecting themselves from ‘sleeper’ infections. With ‘badger blame’ used as a default cause by employing unscientific deductions. Published work explains different interpretations (Sandhu et al 2025).

Published journal studies can only try to crudely estimate the frequency with which transmission occurs, nor the exact route or rate. Their capacity to show the route of transmission of pathogen between hosts is still in its relative infancy and requires intensive studies over many years. They are constrained by accuracy in controlling and sampling multi-host situations in varied commercial settings over relatively long periods of space and time. Study outcomes are dependent on choices made within complex models that are often not clearly identified or published, are speculative, and should be considered with utmost caution. Most papers since 2014 do flag this heavily but observers may try to quote them selectively. The results reported by WGS studies are not consistent, with differing conclusions.

Some of the WGS studies refer to and are parameterised with results from the still uncorrected RBCT analyses in their modelling, which subsequent to successful challenge, should now be seen as scientifically unsupported. Many use the RBCT’s supposed benefit of badger culling as inference in introductions, discussions and conclusions and are now out of date.

The unpopularity of vaccination with …… well almost everybody

Since the 2020 Next Steps policy revision, Defra have begun slowly to promote badger vaccination, investing in pilot schemes like VESBA and academic studies like “Investigations on attitudes towards bovine TB control: badger vaccination”, by Henry Grub of Imperial College, which strangely still remains undisclosed, with Defra claiming that they don’t have a copy. Despite this, most stakeholders are opposed to, or at best, lukewarm about it. Farmers, who have been misled over the efficacy of badger culling and other interventions have very mixed views. A lot of work and expense would be involved if they were to adopt badger vaccination, with benefits unclear.

The British Veterinary Association and British Cattle Veterinary Association do not yet seem to have taken on board the new science surrounding ‘ineffective’ badger culling, and apparently have not revised their positions on interventions. Nature conservation organisations vary in their response to badger vaccination. Some Wildlife Trusts seem to support it in an off-hand way on the basis that it is a move away from culling and could help cattle, while some do not. The RSPCA supported it 5 years ago, but no longer seem to and the Badger Trust moved against it in 2024.

The putative benefits of badger culling (and by implication other badger interventions) have been undermined by new analyses over the last few years. It is a complex issue for everybody to access, (see here.) Smaller organisations especially, struggle to get a clear view on the science if they don’t have access to specialist scientific advisors. Whatever the views of the various stakeholders, badger vaccination leaves significant blame for disease transmission with badgers. That view is now scientifically unjustified.

The financial cost of badger vaccination

Badger vaccination is not a cheap option. The £1.4m badger vaccination trial underway in Cornwall is tiny relative to the landscape scale badger vaccination that it was suggested would be needed to vaccinate badgers in areas coming out of culling in the HRA. And the Junior Minister has confirmed it will not show if it can have an effect on cattle TB rates.

Defra have agreed a contract of £1.8 Mn for the supply of badger BCG vaccine for the next 5 years, and at least £18 Mn for its use over 4-6 years. They have ordered £200,000 of Badger BCG for 2026 from the manufacturer AJ Vaccines in Denmark (Defra FOI). With estimates for the cost of one badger BCG dose at around £33, the aim seems to be to vaccinate around 6,000 badgers. This will increase the number of badgers vaccinated above and beyond that vaccinated in small schemes in, for example nature reserves, which has been by about 25%: from around 3,000 to 4,000 badgers. The result amounts to ‘vaccination lite’ – a tokenistic approach that reflects the scientific lack of confidence in it having any value, (see Farmer Weekly).

The vaccine cost is of course only part of the spend; labour, traps and other associated costs can bump up the price to several hundred pounds per badger. One abandoned Welsh government program in 2015 estimated its costs at over £800 per badger and the maths suggests the new vaccination costs will be similar.

The practical challenges of vaccinating large number of badgers over a large area

The logistics of a vaccination project over a large area looks daunting. Vaccinators need to be trained. Sett locations and access for cage placement and pre-baiting need to be well understood. Permissions for access need to be managed. This will incur further cost. It remains to be seen whether this is feasible within an already sceptical industry, and with volunteers luke-warm at best, about getting dragged-in.

Ethical consideration of interfering in a population of wild animals

Then there is the question of the ethics of interfering with a wild animal population without good reason. Badgers, while susceptible to bovine TB, are relatively resilient to it and may carry several strains around. Their life expectancy is sufficiently short that they are unlikely to die from infection. Despite wild claims, including those in published literature, they have not been shown to be a ‘self-sustaining’ or a maintenance reservoir for bTB infection. It is likely to fade down and out once cattle are clear – in a similar way to that seen in possums in New Zealand. Without re-infection from cattle, it is likely that the disease would die down naturally. Benefits to the badger population from vaccination are unknown, but could be improved health and improve fecundity.

Just not necessary…….

Recent re-analyses (here and here) of badger culling trials have shown that there is no proof of any benefit to cattle from badger culling, and measurable benefit from badger vaccination is unlikely too. From the evidence, it is not justifiable to embark on a hugely expensive and intrusive badger vaccination programme, the benefits of which are dubious, and according to past approaches, unquantifiable. It is just more squandering of public funds when the failings of the current cattle testing system remain poorly addressed, yet are so plain to see.

References

Benton CH, Phoenix J, Smith FA, Robertson A, McDonald RA, Wilson G, Delahay RJ. Badger vaccination in England: Progress, operational effectiveness and participant motivations. People and Nature. 2020 Sep;2(3):761-75.

Langton, Tom, 2021. Where is the March 2020 ‘Next Steps’ policy trying to take us?, YouTube video of Voices for Badgers

Langton, Tom, 2025. Cattle tuberculosis; badgers finally in the clear. British Wildlife Newsletter online 28.11.25.

Robertson A, Chambers MA, Smith GC, Delahay RJ, Mcdonald RA, Brotherton PN. Can badger vaccination contribute to bovine TB control? A narrative review of the evidence. Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 2025 May 1;238:106464.

Sandhu P, Nunez-Garcia J, Berg S, Wheeler J, Dale J, Upton P, Gibbens J, Hewinson RG, Downs SH, Ellis RJ, Palkopoulou E. Enhanced analysis of the genomic diversity of Mycobacterium bovis in Great Britain to aid control of bovine tuberculosis. Front Microbiol. 2025 Mar 25;16:1515906. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2025.1515906. PMID: 40201440; PMCID: PMC11975571.

First preprinted in December 2022, a comprehensive re-evaluation of the RBCT was published in July 2024 in Nature Scientific Reports (

First preprinted in December 2022, a comprehensive re-evaluation of the RBCT was published in July 2024 in Nature Scientific Reports (

In March 2022, a new study (

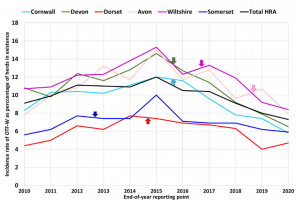

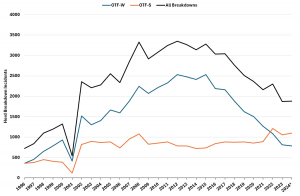

In March 2022, a new study ( Secondly, the 2022 paper looked at the trends over time of disease rates for the same period. Data suggests that the cattle-based testing and movement control measures, including annual tuberculin testing from 2010, were most likely responsible for the slowing, levelling, peaking and decrease in bovine TB in cattle in the High Risk Area (HRA) of England during the study period, in most areas well before badger culling was rolled out.

Secondly, the 2022 paper looked at the trends over time of disease rates for the same period. Data suggests that the cattle-based testing and movement control measures, including annual tuberculin testing from 2010, were most likely responsible for the slowing, levelling, peaking and decrease in bovine TB in cattle in the High Risk Area (HRA) of England during the study period, in most areas well before badger culling was rolled out.

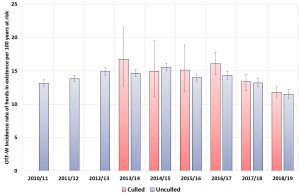

Importantly, APHA epidemiological monitoring of bTB incidence currently focusses on confirmed reactor data (Officially BTB-Free Withdrawn (OTFW)) to report on the progress of disease control. Inclusion of unconfirmed animals in the data (prevalence) indicates that the disease remains largely unchanged after 12 years of Badger Control Policy (BCP) (

Importantly, APHA epidemiological monitoring of bTB incidence currently focusses on confirmed reactor data (Officially BTB-Free Withdrawn (OTFW)) to report on the progress of disease control. Inclusion of unconfirmed animals in the data (prevalence) indicates that the disease remains largely unchanged after 12 years of Badger Control Policy (BCP) (

Back in the day, and well before their ‘not-so-sensible after all’ 2001 merger with the Department of Environment, Transport and the Regions (DETR), the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, (MAFF), were influential in deciding what government should do about badgers.

Back in the day, and well before their ‘not-so-sensible after all’ 2001 merger with the Department of Environment, Transport and the Regions (DETR), the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, (MAFF), were influential in deciding what government should do about badgers.