How did we get here?

Back in 2020, Defra were not pleased. Boris Johnson had forcibly overruled Defra Minister George Eustice to impose a gradual move from badger culling to badger vaccination (BV). Defra were not happy about this because their 2018 ‘Godfray’ review had stated, (in this case correctly), that badger vaccination had unknown efficacy in terms of reducing cattle TB. Industry had ‘no appetite’ for BV. Funds and training for experimentation with it at scale were ruled out, making implementation impossible.

Meanwhile, the National Farmers Union (NFU) and pro-cull lobbyists who heavily influence Defra, were happy to see tens of thousands of largely healthy badgers shot each autumn, and were in no mood to swap their guns for vaccine.

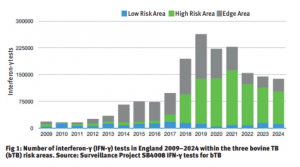

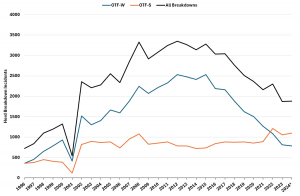

But there were no grounds for optimism that the bovine TB (bTB) policy was fully effective and sufficient. While bTB levels, as recorded by Defra’s increasingly wobbly headline measure ‘herd incidence rate’ 0TF-W (confirmed) were coming down with better testing, OTF-S (so-called ‘unconfirmed’) cases were slowly rising. Failure of the tuberculin skin test (SICCT) to sufficiently detect infected cows was becoming more and more obvious to anyone looking responsibly at the problem.

Low Risk Area (LRA) culling slips into the mix

In 2023, the Defra plan seemed to be to keep BV as a small ‘also ran’ badger intervention in a few locations, like it’s small Sussex ‘VESBA’ pilot study (see here). With the 2024 general election in view, Defra tried to side-step the BV plan to enable something called ‘targeted’ culling. This exploited a loophole that had been slipped into the 2020 policy. It allowed for the culling of badgers where APHA claimed assessment indicated ‘need’ (see here). This new culling sideline was built on the hopelessly speculative Low Risk Area (LRA) culling policy which blamed badgers for the spread of TB once it had been introduced via cattle to remoter areas. Clusters of new infections were termed ‘hotspots’. The new policy involved culling up to 100% of badgers in large core areas. It is not possible to demonstrate any disease benefit from such approaches, but this did not stop APHA and Natural England claiming that it was a success, on expectation alone. This was actually a policy with no scientific way to measure success, as a detailed technical review (that Defra and Natural England simply decided to ignore) pointed out (see here).

Chief Veterinary Officer ‘targeted culling’ plans rejected

To permit ‘targeted culling’, Defra and Natural England had to dump their ‘uncertainty’ standards, as again there was no certainty or even likelihood of efficacy. They rejected any dialogue over the issue. Instead a public consultation attempted to give the Chief Veterinary Officer sweeping powers to establish badger culling at will, and without referral.

The ‘cull at will’ endgame of the badger control policy ran into problems in May 2024 when Rishi Sunak called the general election early, and Labour exposed the badger culls as ‘ineffective’ in their manifesto. Unfortunately, Labour’s full grasp of the science and mechanics of the bovine TB and badgers issue was still hampered by two decades of entrenched thinking by Defra’s civil servants, including in and out of house vets and academics. These individuals must have been fearful of how two and a half decades of research, now looking tatty under close independent scrutiny (see here), had created a complex and flawed demonisation of badgers, and had heavily polarised stakeholders. The frittering of so many £ Billions without coherent results, plus stakeholder misery, might have to be accounted for one day too.

The July 2024 election brought both a hiatus and a degree of common sense to the situation, with targeted culling proposals scrapped, allowing Defra to kick the confused impasse into the long grass for a while. For appearances, Natural England dredged up yet more Heath-Robinson and selective scientific opinion to justify pulling out of culling a few years early. But they were quickly slapped down by Defra who prioritised giving farmer ‘certainty’ over science – intensive and supplementary culling continued. They also gave in to industry pressure to start a new LRA cull in Cumbria (see here) based on yet more speculative guesswork. The unimpressive results of LRA culling were ignored. With hindsight (and some Ministerial insight, see Spectator article), it seems that a shady pre-election deal by Steve Reed with the NFU in 2023 was another reason for the continuation of the intensive and supplementary culls. Although unknown to NFU, it is likely that giving farmers their last couple of years of culling may have been a ‘softener’ to the ‘surprise’ announcement of on farm inheritance tax in October 2024.

2025 Policy review update adds to the confusion

New Minister Daniel Zeichner, unaware of the uncertainty and shifting science around the issue, reappointed the same bTB science panel chosen by Michael Gove to deliver the Conservative Defra agenda. Thus Prof Godfray was reappointed as panel chair, and Defra picked up the reigns again. The Godfray panel needed to massage their 2018 ‘don’t know’ view on BV efficacy into a new policy direction; they obliged in their 2025 review update, contradicting the clear lack of credible supporting evidence. After the election in 2024, and before the re-appointments, Defra had visibly signalled a BV policy direction, taking it as read that it could work. It took time and legal pressure for Defra to admit that the APHA’s ‘Birch’ paper could not link badger culling 2013-2020 to bTB OTF-W decline, reversing Defra’s embarrassing media spin. But Defra persisted with their vague 2020 assumption that BV could reduce disease in cattle, and this is the direction they were pointing.

On 30th August 2024, new Minister Daniel Zeichner promised a ‘strategy refresh’ – although large parts of the 2018 review were either already significantly obsolete or outdated. There would be a year of consultation with key ‘stakeholders’. It all sounded very fair.

But the dozens of people who were cherry picked to ‘co-design’ the refreshed strategy were very close to Defra and under their influence & control, or from industry. Across 2025, Defra paid external agencies to question these favoured representatives in stage-managed workshops, to help rubber stamp its vision of the future. The NGO wildlife sector were struggling to form a collective voice and to be heard. By the autumn they began to complain more visibly about being excluded from the consultation process. Only the Westminster Hall Debate in October 2024 created and promoted by Protect the Wild gave hope that an end to the madness of badger culling was both possible, and in fact was the pre-election promise to be honoured.

Keeping culling alive

Yet despite all this, Defra, were still unhappy. They were trying to keep the door to all badger interventions well and truly open. They placated the NFU with promises that it would be alright in the end, with agri-eyes beginning to shift towards Reform Party politics, and they maintained their scientific position on need for intervention.

The Godfray panel review update had predictably been encouraged to keep the need for all badger interventions alive, as both a face-saving exercise and Defra/NFU wish-list option. They also floated the vastly expensive Test Vaccinate Remove (TVR) option. TVR has uncertain outcomes and no proof of principle, but it kept badger culling ‘on the table’ for pro-cullers. This is despite a recent report on a large scale study in Northern Ireland that could demonstrate no evidence of any clear bTB cattle benefit. The obliging Godfray panel provided Defra with the pathway to give the NFU what they might wish for; a TVR pilot in 2026 or 2027, testing the resolve of Labours political position.

Meanwhile, Defra had organised a return to crudely estimating badger density in the winter of 2025, based on sett activity. Under FoI they claimed not to be estimating badger numbers. This gave them the appearance of being busy, taking the focus away from spending too much time on a stagnating policy, as disease control began to flatline. They also decided to push out on badger vaccination with a £1.4 Mn project in Cornwall. This involved paying the NFU to see if Cornish farmers might accept BV if told it might help reduce bTB in cattle, along the lines of the inconclusive VESBA Sussex badger vaccination project, where intensive use of gamma tests had shown some value.

In reply to a parliamentary question by Baroness Bennett on 30th July 2025, junior Minister Sue Hayman denied that the Cornish vaccination project would be assessed in terms of cattle disease efficacy, conflicting with what local farmers had been told and were saying to the press. It seemed a strange statement that may yet prove to be untrue. It seems that data generated by the project is likely to be added to APHA’s national BV research project (see below).

As 2025 ended, a freedom of information response revealed what Defra’s plan was all along. Defra had announced the allocation of around £20 Mn over 4-6 years to BV. This is not a huge amount given the mountain of work required (see here), with the cost per vaccinated badger estimated at nearly £800 once staffing, logistics and operational costs are taken into account.

A secret study uncovered

But what were Defra really up to? The clue was that APHA had started to use any and all recent data from BV to look for change in nearby TB herd breakdowns and compare it against places without BV. Defra promoted media coverage of a ‘record increase’ in BV which meant very little as the numbers were still relatively tiny. There was no sign of any attempt to replace culling with BV. Why?

What Defra were pursuing was an in-house plan to try to justify the concept of BV. They were aware that their scientific basis for BV was as weak or weaker than it was for culling, and that government needed better evidence. A legal challenge on this issue was possible, either from NFU or the voluntary sector. Some of the APHA staff with past publications who were invested in claiming a need for badger interventions, cobbled together a narrative article about it. They were trying to argue a case for BV that the Godfray panel update could champion (see here).

This arrived just in time to be quoted by the ‘Godfray panel’, who also commissioned a further article using simulated data to try to suggest that badger culling after 2013 might not have been ineffective. This also supported a case that BV vaccination might not be wholly useless (see here). All looking a bit desperate.

Defra’s main plan now is to expand its farm-based badger vaccination analysis. They are going to compare farms/farm clusters in places where badger vaccination has been done since around 2020 (in Cumbria, Cheshire, Sussex, Cornwall and elsewhere) with those where no badger vaccination has been done. The aim is to try to create some science to show BV efficacy. The problem? Such an analysis will be confounded by its inability to control for important variables such as cattle movements and frequency and type of testing. It is all but impossible to undertake meaningful analysis in such circumstances; see APHAs previous efforts on badger culling here, here and here.

Defra have disclosed in recent weeks:

The analytical approach being developed by APHA involves quantifying exposure to badger vaccination at a herd level, rather than by looking at large contiguous areas, which was the approach taken for the Badger Control Policy.

Quantifying badger vaccination exposure at a herd level means that cattle herds potentially affected by disparate small scale badger vaccination programmes can then be combined in a single analysis.

The aim of the analysis is then to compare these cattle herds to those where vaccination did not take place, potentially controlling for the numerous other factors which may influence bTB risk.

This approach is challenging, but it is hoped that this can develop a statistical framework to estimate the effect of badger vaccination in the future. In addition to the approach detailed above, there may also be further analytical approaches that can be applied to larger contiguous badger areas which may become more common as the vaccination policy progresses.

Can APHA bTB science ever be trusted again?

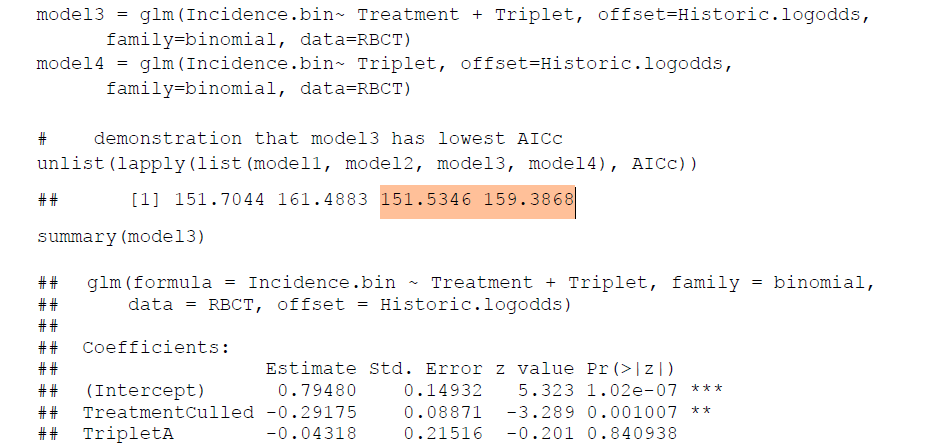

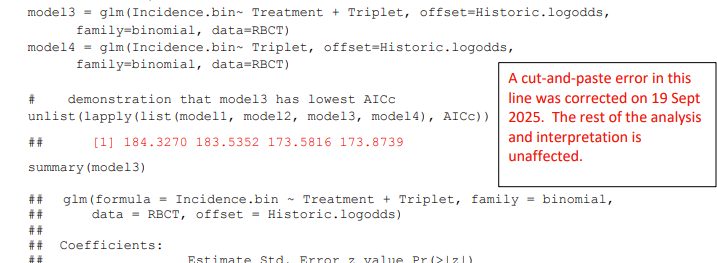

Defra have again kept data secret, preventing external scrutiny. They may not have enough data from badger vaccination to-date, so might want to add information they will be collecting over the next few years. Defra should know that at the herd level, analysis of proactive badger culling data from the RBCT showed no disease benefit. They are withholding any post-2013 herd level analysis from intensive badger culling, probably because it shows no effect.

One potential problem is that the data available is large enough to produce a range of results, according to how it is selected and handled. This is why it should be done openly according to a pre-planned analytical protocol, and not exclusively by those with interest in outputs that support previous beliefs and perceptions. This, as international experts are pointing out, is where everything has gone wrong in the past (see review history for Torgerson et al 2025, explained here).

Zoologists and statisticians who have produced work supporting badger interventions in the past, that have now been shown to be equivocal, should not be the only individuals involved in such work. So far Defra have suggested that decisions on such appointments may not be entirely in their hands, which is suspicious. Further information is being sought on these important points of principle.

Defra’s tendency to throw ‘all the tools in the box’ together at bovine TB, rather than the right tools, means that it is not possible to tell which intervention has had effect and which has not. There is a bigger problem in terms of learning and adapting, when the combination of tools is not working well enough. This is no way to proceed and those in charge badly need to overhaul to an ineffective system.

More unscientific publications?

As indicated above, industry may have made the study of BV a condition of them not opposing it. Keeping BV on a small localised scale could be a government strategy to simply wait for a future government to allow a return to intensive badger culling. After all, the Godfray panel claimed that culling was ‘likely’ to have had an effect, despite the lack of credible scientific evidence. Defra don’t seem to want this advertised because it undermines their old beliefs in the role of badgers in bTB, that are still being used to sustain culling in the Low Risk Area. Having trained farmers and veterinarians for decades to believe that badgers have driven the spread of disease, they have no appetite for admitting they were wrong and re-training them out of a bad habit.

Pretences and deceptions – will they continue?

Pretending that BV can have an effect on cattle TB without evidence is untenable. Having a review panel express their opinion in a way that contradicts that lack of evidence has been unhelpful. Are we really going to see a new chapter of misleading science coming out of Defra?

There are some bad signs. The strategy refresh consultation over last year ignored key scientific stakeholders and refused to consider advice outside its 2018 review update. This is despite that review containing multiple errors and misleading statements, only one of which has been corrected to-date.

Is there no one in government with the moral compass to do the right thing and start again? Has the strategy been refreshed or is it simply being pushed further into the mire?

Boyd suggested that there is continuing pressure to produce results to fit a political agenda, mistakes are commonplace, they continue to be made, and the way to prevent the same thing from happening in the future is far from clear. He wished he had known more about Bovine TB before taking on his role. You can read more about who said what

Boyd suggested that there is continuing pressure to produce results to fit a political agenda, mistakes are commonplace, they continue to be made, and the way to prevent the same thing from happening in the future is far from clear. He wished he had known more about Bovine TB before taking on his role. You can read more about who said what  Supplementary badger culling was authorized for a further year on June 1st. Natural England‘s scientific rationale for licensing did not take into account the

Supplementary badger culling was authorized for a further year on June 1st. Natural England‘s scientific rationale for licensing did not take into account the  On June 12th, a day later, the

On June 12th, a day later, the

On 13th October, there was a much awaited Westminster Hall debate (view

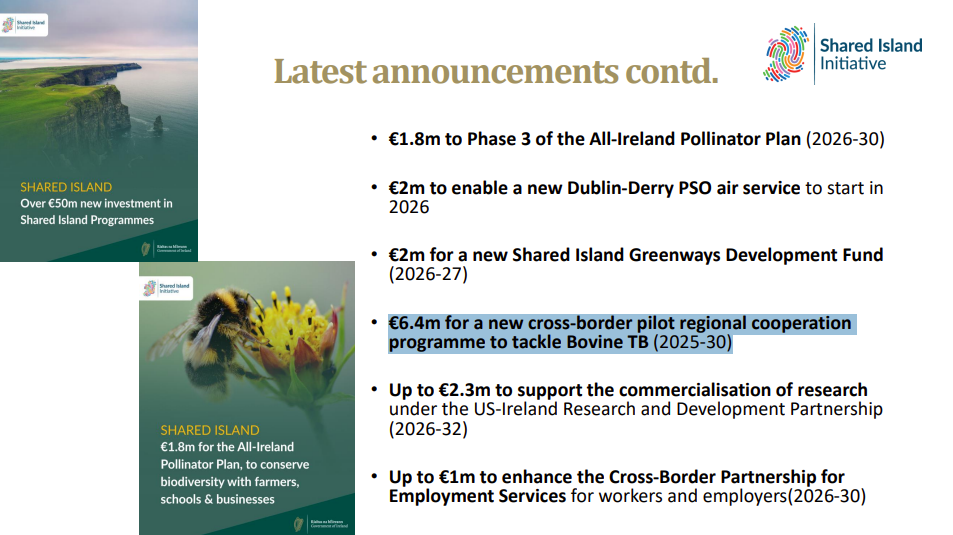

On 13th October, there was a much awaited Westminster Hall debate (view  Meanwhile in Northern Ireland, a Parliamentary question by Miss Michelle McIlveen (from the DUP) tabled on November 18th made it clear that a €6.4m investment for a cross-border pilot regional cooperation programme on tackling bovine TB had been secured, with use of TVR as an experiment. This was leaked by the Ulster Farmers Union who wanted intensive badger culling and exposed DAERA’s attempt to instigate lethal interventions, despite previous undertakings not to do so without consultation.

Meanwhile in Northern Ireland, a Parliamentary question by Miss Michelle McIlveen (from the DUP) tabled on November 18th made it clear that a €6.4m investment for a cross-border pilot regional cooperation programme on tackling bovine TB had been secured, with use of TVR as an experiment. This was leaked by the Ulster Farmers Union who wanted intensive badger culling and exposed DAERA’s attempt to instigate lethal interventions, despite previous undertakings not to do so without consultation. A letter published 13th December in Vet Record (

A letter published 13th December in Vet Record ( It is thanks to all of you that we have collectively been able to protest, campaign, lobby, publish and report, and we can only hope that next year finally sees some truth and honesty from those who would seek to cover up the sins of the past. Particular thanks are due to all at Protect The Wild for their relentless public awareness work, especially the successful government petition and Westminster debate, backed by the general public. Also to Betty Badger (aka Mary Barton) and friends who maintained the Thursday vigil outside Defra offices, protesting the injustice (see article in the

It is thanks to all of you that we have collectively been able to protest, campaign, lobby, publish and report, and we can only hope that next year finally sees some truth and honesty from those who would seek to cover up the sins of the past. Particular thanks are due to all at Protect The Wild for their relentless public awareness work, especially the successful government petition and Westminster debate, backed by the general public. Also to Betty Badger (aka Mary Barton) and friends who maintained the Thursday vigil outside Defra offices, protesting the injustice (see article in the

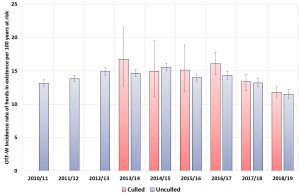

The RBCT had three sets of trial areas; these were pro-active culling (badger density reduced by average 70%, reactive culling (100% culling around breakdown farms only), and no-cull control areas.

The RBCT had three sets of trial areas; these were pro-active culling (badger density reduced by average 70%, reactive culling (100% culling around breakdown farms only), and no-cull control areas. While badgers, like deer and other mammals both domestic and wild can be infected with bovine TB, the extent to which they may be responsible for a small proportion of cattle herd infections, especially in intensive livestock systems is unknown. If it occurs, there is no reliable data available that wildlife transmission to cattle can establish, maintain or perpetuate – this falsehood has been normalised by a few authors keen to bolster wrong claims. Indeed the

While badgers, like deer and other mammals both domestic and wild can be infected with bovine TB, the extent to which they may be responsible for a small proportion of cattle herd infections, especially in intensive livestock systems is unknown. If it occurs, there is no reliable data available that wildlife transmission to cattle can establish, maintain or perpetuate – this falsehood has been normalised by a few authors keen to bolster wrong claims. Indeed the  First preprinted in December 2022, a comprehensive re-evaluation of the RBCT was published in July 2024 in Nature Scientific Reports (

First preprinted in December 2022, a comprehensive re-evaluation of the RBCT was published in July 2024 in Nature Scientific Reports (

In March 2022, a new study (

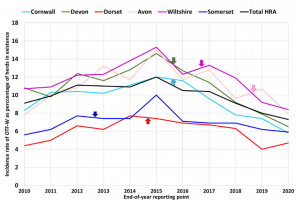

In March 2022, a new study ( Secondly, the 2022 paper looked at the trends over time of disease rates for the same period. Data suggests that the cattle-based testing and movement control measures, including annual tuberculin testing from 2010, were most likely responsible for the slowing, levelling, peaking and decrease in bovine TB in cattle in the High Risk Area (HRA) of England during the study period, in most areas well before badger culling was rolled out.

Secondly, the 2022 paper looked at the trends over time of disease rates for the same period. Data suggests that the cattle-based testing and movement control measures, including annual tuberculin testing from 2010, were most likely responsible for the slowing, levelling, peaking and decrease in bovine TB in cattle in the High Risk Area (HRA) of England during the study period, in most areas well before badger culling was rolled out.

Importantly, APHA epidemiological monitoring of bTB incidence currently focusses on confirmed reactor data (Officially BTB-Free Withdrawn (OTFW)) to report on the progress of disease control. Inclusion of unconfirmed animals in the data (prevalence) indicates that the disease remains largely unchanged after 12 years of Badger Control Policy (BCP) (

Importantly, APHA epidemiological monitoring of bTB incidence currently focusses on confirmed reactor data (Officially BTB-Free Withdrawn (OTFW)) to report on the progress of disease control. Inclusion of unconfirmed animals in the data (prevalence) indicates that the disease remains largely unchanged after 12 years of Badger Control Policy (BCP) (

At the Westminster Hall Debate on the 13th October, Angela Eagle the Defra Minister of State confirmed that the badger cull would come to an end in February 2026 in all but one area. Cull Area no. 73, south of Carlisle, was initiated by Labour as a new cull zone last year (around what was called hotspot 29). It is large (183 sq km), and it can potentially run for up to five years (to 2029) with a 100% kill target, and some vaccination of any survivors. Voters have been incensed that despite Labours pledge to stop the culling that they described in their manifesto as ‘ineffective’, not only has it continued, but this new zone has been added..

At the Westminster Hall Debate on the 13th October, Angela Eagle the Defra Minister of State confirmed that the badger cull would come to an end in February 2026 in all but one area. Cull Area no. 73, south of Carlisle, was initiated by Labour as a new cull zone last year (around what was called hotspot 29). It is large (183 sq km), and it can potentially run for up to five years (to 2029) with a 100% kill target, and some vaccination of any survivors. Voters have been incensed that despite Labours pledge to stop the culling that they described in their manifesto as ‘ineffective’, not only has it continued, but this new zone has been added.. And Natural England (NE) who issue the culling licenses, decided to ignore an independent expert report (

And Natural England (NE) who issue the culling licenses, decided to ignore an independent expert report ( So the only detailed technical report by non-vested scientists was discounted because it showed a picture of the methodology being employed. This decision lacks impartiality, but it is consistent with the biased and selective use of science throughout the various government justifications provided for culling. Let’s not forget, Natural England were found in breach of their statutory duty in the High Court (2018) (

So the only detailed technical report by non-vested scientists was discounted because it showed a picture of the methodology being employed. This decision lacks impartiality, but it is consistent with the biased and selective use of science throughout the various government justifications provided for culling. Let’s not forget, Natural England were found in breach of their statutory duty in the High Court (2018) (

The Westminster Hall debate of the Protect the Wild petition, held on 13th October, was a significant improvement on previous badger cull debates. The majority of voices spoke earnestly about a wish to stop badger culling and address TB testing failures as soon as possible. There wasn’t a repeat of the nonsense we have previously seen; “too many badgers” and “killing hedgehogs, bees and ground nesting birds”. And the Minister Angela Eagle concluded by committing to ending the badger cull by the end of this Parliament (2029), possibly hinting at terminating remaining licenses to bring all culling to a conclusion in 2026.

The Westminster Hall debate of the Protect the Wild petition, held on 13th October, was a significant improvement on previous badger cull debates. The majority of voices spoke earnestly about a wish to stop badger culling and address TB testing failures as soon as possible. There wasn’t a repeat of the nonsense we have previously seen; “too many badgers” and “killing hedgehogs, bees and ground nesting birds”. And the Minister Angela Eagle concluded by committing to ending the badger cull by the end of this Parliament (2029), possibly hinting at terminating remaining licenses to bring all culling to a conclusion in 2026.