January

On 30th January 2025, Defra issued Terms of Reference for a ‘comprehensive new bovine TB review’, as part of a refreshed bTB eradication strategy, first announced in August 2024 (see here). A panel for the new review, was to be chaired, as previously, by Professor Sir Charles Godfray. It was his work (with others) and his advice that was used to help establish and maintain badger culling from 2013. Godfray, rooted at Oxford University, has long been associated with those designing and undertaking aspects of the controversial Randomised Badger Culling Trial (1998 – 2005). Indeed, he chaired its so-called ‘independent’ statistical audit (Godfray et al 2004).

Following discovery of serious statistical irregularities in the key 2006 RBCT proactive badger culling publication in more recent years, lead author Christl Donnelly, Professor of Applied Statistics at Oxford University, recused herself from the panel. But surprisingly, she was replaced by a recently arrived colleague Professor Sir Bernard Silverman FRS, Emeritus Professor of Statistics, also at Oxford University.

Other panel members, of what later in the year became known as the Strategy review ‘refresh’ or ‘update’, were the same as in the 2018 review: Professor Glyn Hewinson CBE of Aberystwyth University, Professor Michael Winter OBE University of Exeter and Professor James Wood OBE of University of Cambridge. So once again, it was largely the same set of academics as appointed in 2017, looking at the science in which they personally have a historical interest and potentially, future stake. With the new findings to be read alongside the earlier review, despite much of the 2018 material being superfluous or out of date.

Defra refused to adequately address multiple protests against the panel appointments for ‘conflict of interest’, simply saying those concerned were ‘esteemed’ and ‘distinguished’; that was enough for Defra. They later said the checking system relied on members own self-referral.

February

On February 15th, Prof Ian Boyd, past Defra Chief Scientific Advisor (as Badger culling was developed) and major influence in the culling of over 250,000 mostly healthy badgers), was the guest of Sir Charles Godfray in Oxford, for Boyd’s book promotion (Science and Politics). Bovine TB and badgers was the most mentioned topic, but the wider issue was of politics distorting the scientific process in general. Boyd’s main thrust appeared to be to point a finger at politicians (‘charlatans’ he calls them in the book) and also at the Royal Society.

Boyd suggested that there is continuing pressure to produce results to fit a political agenda, mistakes are commonplace, they continue to be made, and the way to prevent the same thing from happening in the future is far from clear. He wished he had known more about Bovine TB before taking on his role. You can read more about who said what here.

Boyd suggested that there is continuing pressure to produce results to fit a political agenda, mistakes are commonplace, they continue to be made, and the way to prevent the same thing from happening in the future is far from clear. He wished he had known more about Bovine TB before taking on his role. You can read more about who said what here.

March-May

Spring 2025 saw new scientific papers on badger vaccination, the Test / Vaccinate / Remove (TVR) approach and even badger contraception. This flurry of papers from government scientists seemed to be looking to satisfy the politicians stated aim to switch from badger culling to non-lethal methods. But with TVR lurking in the background as a potential closet return to culling.

Robertson et al (2025) claimed that “Modelling studies evaluating different strategies for controlling TB in badgers predict that badger vaccination will reduce TB prevalence in badger populations and lead to corresponding reductions in cattle herd disease incidence.” But without direct evidence and yet again stretching and trying to normalize APHA’s efforts to cause-argue policy from equivocal science, dubious assumptions and partisan models. Along exactly the same lines (and almost as if to provide Boyd fresh evidence for his government science take-down), Smith & Budgey (2025) reported that a “combined approach of vaccination and selective culling (TVR) based on test results may give a more robust method of disease management than just vaccination on its own.”

The preprint by Palphramand et al (2025) (to be published in Science Direct Jan 2026) suggests that “co-administration of BCG vaccine and and GonaCon (a contraceptive) enhances the protective effect of the booster vaccination.” This is research work carried out on a small captive population of badgers caught from the wild.

June

Supplementary badger culling was authorized for a further year on June 1st. Natural England‘s scientific rationale for licensing did not take into account the Torgerson et al (2024) preprint which highlighted serious statistical issues with the Mills et al (I & II) (2024) upon which they relied. In doing so, it continued with its policy of ignoring key stakeholders and relevant evidence and simply obeying Defra’s mandate to carry on culling thousands more badgers, despite mounting evidence against it’s efficacy.

Supplementary badger culling was authorized for a further year on June 1st. Natural England‘s scientific rationale for licensing did not take into account the Torgerson et al (2024) preprint which highlighted serious statistical issues with the Mills et al (I & II) (2024) upon which they relied. In doing so, it continued with its policy of ignoring key stakeholders and relevant evidence and simply obeying Defra’s mandate to carry on culling thousands more badgers, despite mounting evidence against it’s efficacy.

On 11th June, The Royal Society published Torgerson et al (2025), undermining the RBCT conclusions of a disease benefit from proactive badger culling. This effectively removed any credible scientific rationale for it. Defra did not respond to the new publication. You can read more about this paper & its significance as a watershed moment for British biological sciences here.

On June 12th, a day later, the BBC reported that “Farmers to get support vaccinating badgers”, confirming that badgers would continue to take substantial blame for bovine TB in cattle. Clearly, Steve Reed, Daniel Zeichner, and the Defra Ministers continue to be misled by their personnel who are unable to admit (due perhaps to responsibility for financial waste and pride / position), that badger culling has been both unnecessary and worthless.

On June 12th, a day later, the BBC reported that “Farmers to get support vaccinating badgers”, confirming that badgers would continue to take substantial blame for bovine TB in cattle. Clearly, Steve Reed, Daniel Zeichner, and the Defra Ministers continue to be misled by their personnel who are unable to admit (due perhaps to responsibility for financial waste and pride / position), that badger culling has been both unnecessary and worthless.

July

On 30th July, Baroness Bennett of Manor Castle Green received a reply to her written Parliamentary Question:

“To ask His Majesty’s Government what assessment they have made of the paper by Torgerson and others published in the Royal Society Open Journal on 11 June claiming that other studies of badger culls contain methodological weaknesses; and what plans they have, if any, to ensure that the Cornwall Badger Vaccination Pilot has a peer-reviewed protocol before any work can continue.”

Junior Minister Sue Hayman replied for the government saying “Unlike previous badger culling studies, the Cornwall Badger Project is focused on testing different methods of delivering badger vaccination, rather than evaluating the impact on bovine TB in cattle.”

So all the Cornish badger vaccination project can hope to show is whether Cornish farmers are prepared to engage.

August

In late July/early August it was widely reported that Jeremy Clarkson’s Diddly Squat Farm in Oxfordshire (subject of TV show ‘Clarkson’s Farm’) had gone down with bTB reactors, having bought cattle from sources with relatively recent breakdowns.

Whilst The Daily Telegraph foolishly speculated that “the presenter was unable to stop transmission of the bacteria from badger to cow”, epidemiologist James Wood on Farming Today said “The challenge is with this [testing] system, the controls are imperfect, so that when we clear a farm with TB we know that a proportion that maybe as high as 25 or 50%, a proportion will have one or two animals that are still likely to be infected.” Clarkson expressed doubt about testing and a need for information and then went silent as several of his stock were destroyed. No doubt Defra were nervous of the high profile of the story, and aware of how its flawed bTB testing system could be more widely exposed. See our blog on the story here.

September

In September, the delayed (due in June) Godfray review update was published (see here). Key points:

- It confirms (page 75) in a massive ‘wake-up’ finding, that Torgerson et al (2024 & 2025) papers do show that the key 2006 RBCT proactive badger culling paper by Donnelly and others in Nature journal got the modelling hopelessly wrong. This has massive implications for a wide number of papers and official reports that have used that paper’s calculations to build further models and create policy and financial estimates.

- Remarkably, it went to the lengths of producing its own new (binomial) model, claiming a culling benefit, but with lower statistical significance (it has gone from P < 0.005 to P < 0.05). However, there were mistakes and multiple issues with this model that were outlined in a new preprint by Prof Paul Torgerson (here), also posted September 2025. There has been no subsequent response from Defra. The authors have made some rudimentary remarks about agreeing to differ and the differences being subtle, which they certainly are not.

- The manner in which the new model was checked before publication is subject to close scrutiny due to suspected irregularities.

- The “bTB perturbation effect hypothesis” (used to justify culling healthy badgers) became un-evidenced, as it is statistically unsupported by Godfray’s model (as well as Torgerson’s models), undoing the RBCT conclusions even more comprehensively (see here) and triggering calls for retraction of key papers (see here).

- It failed to deliberate on the ‘confirmed’ versus ‘unconfirmed’ continuum in the identification of reactors, that was clarified in 2018, but not by the 2018 review. This obfuscates on what is a central issue, both in bTB testing and badger culling science. The panel just feebly recommended further research. This is despite Natural England formally asking the Godfray panel to focus on it.

- It inexcusably repeated errors in Birch et al (2024), notably the under-declaration of interferon gamma use (see here and here) which was introduced at the same time as badger culling and makes it impossible to separate the effects of badger culling from cattle measures. It also mistakenly claims it evaluated “before-after differences in treated units with those in untreated units” which is a very worrying mis-reading of the methods. Birch was a time series study, with no comparison of separate culled and unculled areas.

- It uses an unpublished report that the panel asked specially to be made available (Robertson et al (2025) to claim that Langton et al (2022) may not have detected a disease benefit had there been one. The unconvincing efforts in this preprint have been addressed here (Langton 2025).

October

On 13th October, there was a much awaited Westminster Hall debate (view here) on ending badger culling, precipitated by a 100,000 parliamentary petition coordinated by the successful lobbyists and wild animal protection advocates Protect the Wild. Although the two-hour session was a massive improvement on previous dreadful badger cull debates (reflecting the cull of dinosaur politicians lost in the 2024 general election), it remained (perhaps not surprisingly) ‘behind the curve’ on recently published science. Happily, the majority of voices spoke earnestly about a wish to stop badger culling and address TB testing failures and to manage the disease effectively. Minister Angela Eagle reaffirmed Labours commitment to ending the badger cull by the end of this Parliament, with the possibility of all culls ending in 2026 following a review of the last cull area (no. 73) in Cumbria in the New Year. However, it is likely that Defra will do everything in its power to prevent this, via introducing TVR pilots.

On 13th October, there was a much awaited Westminster Hall debate (view here) on ending badger culling, precipitated by a 100,000 parliamentary petition coordinated by the successful lobbyists and wild animal protection advocates Protect the Wild. Although the two-hour session was a massive improvement on previous dreadful badger cull debates (reflecting the cull of dinosaur politicians lost in the 2024 general election), it remained (perhaps not surprisingly) ‘behind the curve’ on recently published science. Happily, the majority of voices spoke earnestly about a wish to stop badger culling and address TB testing failures and to manage the disease effectively. Minister Angela Eagle reaffirmed Labours commitment to ending the badger cull by the end of this Parliament, with the possibility of all culls ending in 2026 following a review of the last cull area (no. 73) in Cumbria in the New Year. However, it is likely that Defra will do everything in its power to prevent this, via introducing TVR pilots.

Also in October 2025, Prof. Torgerson published a letter in Veterinary Record (see here) reporting his request for a retraction of the Donnelly et al (2006) paper by Nature journal.

November & December

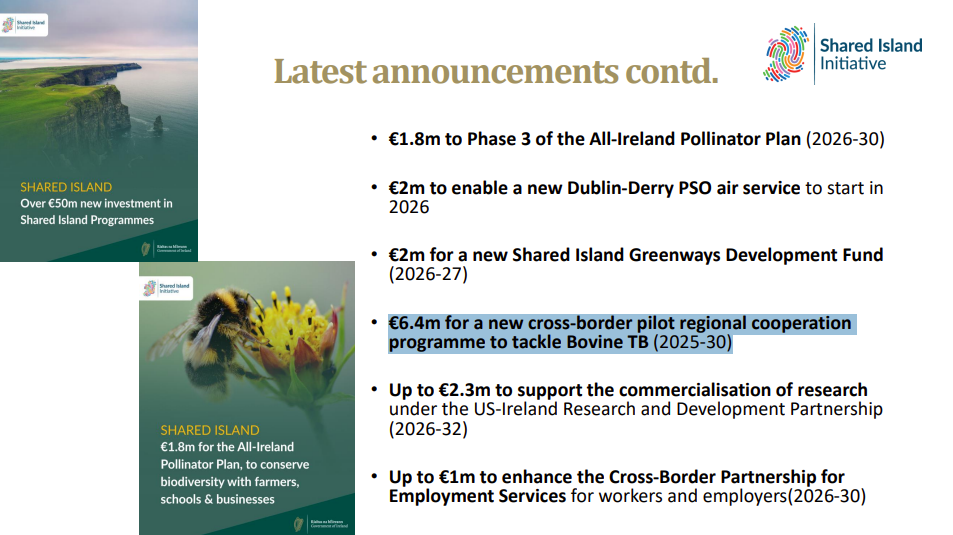

Meanwhile in Northern Ireland, a Parliamentary question by Miss Michelle McIlveen (from the DUP) tabled on November 18th made it clear that a €6.4m investment for a cross-border pilot regional cooperation programme on tackling bovine TB had been secured, with use of TVR as an experiment. This was leaked by the Ulster Farmers Union who wanted intensive badger culling and exposed DAERA’s attempt to instigate lethal interventions, despite previous undertakings not to do so without consultation.

Meanwhile in Northern Ireland, a Parliamentary question by Miss Michelle McIlveen (from the DUP) tabled on November 18th made it clear that a €6.4m investment for a cross-border pilot regional cooperation programme on tackling bovine TB had been secured, with use of TVR as an experiment. This was leaked by the Ulster Farmers Union who wanted intensive badger culling and exposed DAERA’s attempt to instigate lethal interventions, despite previous undertakings not to do so without consultation.

On 2nd December Andrew Muir (Minister of DAERA of Northern Ireland), responding to a further Parliamentary Question about this funding replied that “Wildlife Intervention is a key part of that plan, which is why we will consult on wildlife intervention options in the spring of next year.”

So it looks like badger interventions are part of the bTB control plans in Northern Ireland, going forwards with a clumsy attempt to use TVR as a route towards wider culling. This is the approach already shown to be unnecessary by correct use of RBCT data, the post 2013 industry culling in England and long term badger culling and vaccination in the Republic of Ireland.

A letter published 13th December in Vet Record (here) raised questions concerning the continuation of badger blame following criticisms of the recent Godfray review. A response from the Godfray review panel was published alongside, repeating their view that “reasonable people can disagree about the best way to analyse complex data“. They remain, however, like Defra, unwilling to enter into a discussion on any of the analyses.

A letter published 13th December in Vet Record (here) raised questions concerning the continuation of badger blame following criticisms of the recent Godfray review. A response from the Godfray review panel was published alongside, repeating their view that “reasonable people can disagree about the best way to analyse complex data“. They remain, however, like Defra, unwilling to enter into a discussion on any of the analyses.

The Badger Trust / Wild Justice Judicial Review hearing against Natural England (on an incorrect reason for granting 2024 Supplementary badger cull licences) listed to start on 16th December was postponed due to “a court administrative error”. The case will now be relisted “sometime in 2026”.

And there has been much more going on, bubbling along beneath the surface that is work in progress, and that we will report on when we are able. We had hoped for better in 2025, with the science supporting badger culling now completely undone. But it looks as if it will take a little longer before the fundamental importance of the new publications is understood and accepted.

Thanks go to….

As in previous years, Badger Crowd would like to thank the hundreds of people who have worked together to support this years work to expose and halt the cruel and needless killing of badgers as a part of ineffective livestock disease control. As the mass culling of in the region of 6,000 badgers in 2025/6 is completed at the end of January 2026, there is still no formal recognition from Defra that this has been one of their biggest wildlife blunders.

It is thanks to all of you that we have collectively been able to protest, campaign, lobby, publish and report, and we can only hope that next year finally sees some truth and honesty from those who would seek to cover up the sins of the past. Particular thanks are due to all at Protect The Wild for their relentless public awareness work, especially the successful government petition and Westminster debate, backed by the general public. Also to Betty Badger (aka Mary Barton) and friends who maintained the Thursday vigil outside Defra offices, protesting the injustice (see article in the Spectator). Thanks also to the regular forums of the national ‘Voices for Badgers‘ network, the tireless Oxford Badger Group and so many others who have campaigned, donated and supported. And not to forget those who put endless hours in to protect badgers and their setts from multiple threats in their own areas. A massive shout out too to all those in the field, unblocking illegally infilled badger setts and those opposing snares. New legislation could be on the way – we certainly hope so. Thanks to all for your strength and determination.

It is thanks to all of you that we have collectively been able to protest, campaign, lobby, publish and report, and we can only hope that next year finally sees some truth and honesty from those who would seek to cover up the sins of the past. Particular thanks are due to all at Protect The Wild for their relentless public awareness work, especially the successful government petition and Westminster debate, backed by the general public. Also to Betty Badger (aka Mary Barton) and friends who maintained the Thursday vigil outside Defra offices, protesting the injustice (see article in the Spectator). Thanks also to the regular forums of the national ‘Voices for Badgers‘ network, the tireless Oxford Badger Group and so many others who have campaigned, donated and supported. And not to forget those who put endless hours in to protect badgers and their setts from multiple threats in their own areas. A massive shout out too to all those in the field, unblocking illegally infilled badger setts and those opposing snares. New legislation could be on the way – we certainly hope so. Thanks to all for your strength and determination.

It was the combined care and effort of all those taking a stand, no matter how large or small, that is helping bring mass badger culling to an end in England. We must now continue our opposition to culling in Ireland. We must ensure that accurate science now guides policy away from unnecessary, unverifiable and cruel protected species interventions. Badger culling must not be allowed to continue or ever happen again. There is much work still to be done, but the continued determination and energy of so many can prevail.

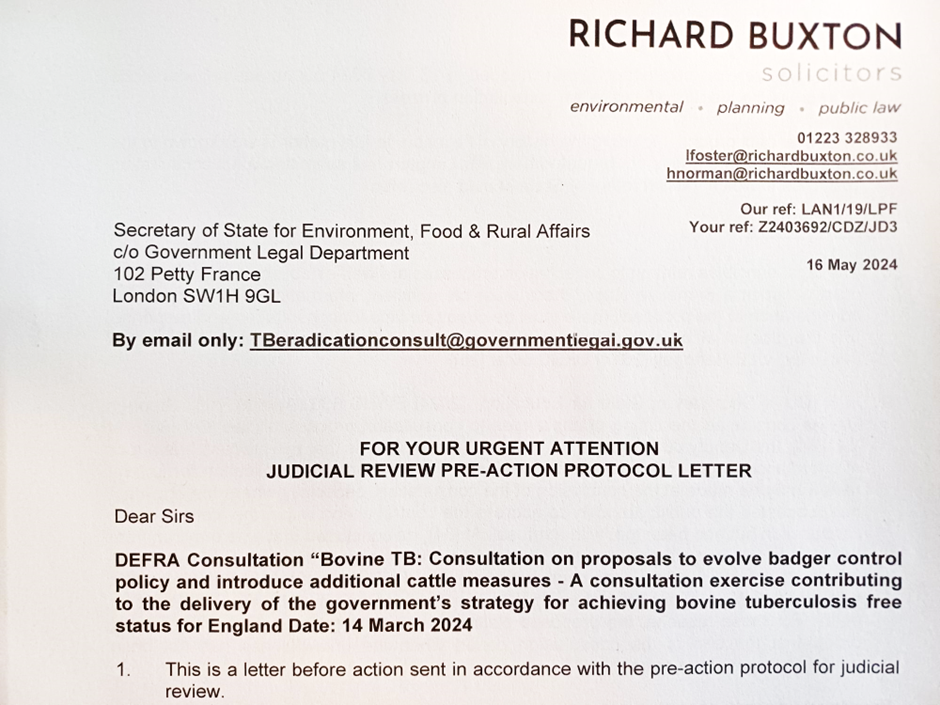

DEFRA’s tactics appeared to be to try to justify badger culling in order to reverse the ‘phasing out’ of badger culling by the 2020 ‘Next Steps’ policy. This was perhaps also addressing the High Court’s expectation, stated 5 years previously, that policy should ‘adapt and learn’ from the results of Supplementary Badger Culling. The DEFRA plan, as revealed on 14th March, was to introduce something called ‘targeted culling‘ (

DEFRA’s tactics appeared to be to try to justify badger culling in order to reverse the ‘phasing out’ of badger culling by the 2020 ‘Next Steps’ policy. This was perhaps also addressing the High Court’s expectation, stated 5 years previously, that policy should ‘adapt and learn’ from the results of Supplementary Badger Culling. The DEFRA plan, as revealed on 14th March, was to introduce something called ‘targeted culling‘ ( The March 2024 DEFRA plan was to allow extensive culling into the future across England at the discretion of the Chief Veterinary Officer, potentially under a general licence, further negating provisions of the Protection of Badgers Act 1992. It looked like Defra were trying to put a policy in place before a General Election, to commence in autumn 2024. The DEFRA plan looked like a normalization of widespread badger culling into the future. Likely to further stimulate illegal badger culling that is now reported to be rife in some bovine TB areas.

The March 2024 DEFRA plan was to allow extensive culling into the future across England at the discretion of the Chief Veterinary Officer, potentially under a general licence, further negating provisions of the Protection of Badgers Act 1992. It looked like Defra were trying to put a policy in place before a General Election, to commence in autumn 2024. The DEFRA plan looked like a normalization of widespread badger culling into the future. Likely to further stimulate illegal badger culling that is now reported to be rife in some bovine TB areas.

Ultimately, the consultation fell victim to the announcement by Prime Minister Rishi Sunak on 22nd May of a General Election on 4th July. This froze consideration of the consultation responses until after the election. The Labour Party manifesto for the 2024 General Election was published on 13th June, and stated its intention to end “ineffective” badger culling, as previously pledged during the 2019 general election. Labour had been keeping very quiet about its position on culling in the months leading up to the election. Presumably this was a tactic to placate the farming vote which was needed before Reform UK Party decided to stand. It appeared to have agreed to keep some badger culling going as a part of a back-room deal with the NFU, a fix that was later exposed by reliable sources (

Ultimately, the consultation fell victim to the announcement by Prime Minister Rishi Sunak on 22nd May of a General Election on 4th July. This froze consideration of the consultation responses until after the election. The Labour Party manifesto for the 2024 General Election was published on 13th June, and stated its intention to end “ineffective” badger culling, as previously pledged during the 2019 general election. Labour had been keeping very quiet about its position on culling in the months leading up to the election. Presumably this was a tactic to placate the farming vote which was needed before Reform UK Party decided to stand. It appeared to have agreed to keep some badger culling going as a part of a back-room deal with the NFU, a fix that was later exposed by reliable sources ( An important new extensive re-evaluation of the Randomised Badger Culling Trial was published in Nature Scientific Reports by Prof Paul Torgerson with others, on 15th July, shaking the foundation stone of Government policy since 2011. It provided further and highly extensive evidence that the role of badgers in bovine TB in cattle was fatally misconstrued, and the problems had not been spotted over 20 years ago (

An important new extensive re-evaluation of the Randomised Badger Culling Trial was published in Nature Scientific Reports by Prof Paul Torgerson with others, on 15th July, shaking the foundation stone of Government policy since 2011. It provided further and highly extensive evidence that the role of badgers in bovine TB in cattle was fatally misconstrued, and the problems had not been spotted over 20 years ago ( Throughout 2023 and 2024 the Oxfordshire Badger Group (OBG), with support from others, had tried to initiate discussion of the RBCT design and findings with Oxford University, but reported a wall of reluctance or silence. Around 7,000 badgers have been shot in Oxfordshire so far. On 18th July OBG presented a petition with over 50,000 signatures to Oxford University School of Biology in central Oxford. OBG called on Oxford University to own what it called “Your Bloody Science” and asked them to “Speak out against badger extermination”, (

Throughout 2023 and 2024 the Oxfordshire Badger Group (OBG), with support from others, had tried to initiate discussion of the RBCT design and findings with Oxford University, but reported a wall of reluctance or silence. Around 7,000 badgers have been shot in Oxfordshire so far. On 18th July OBG presented a petition with over 50,000 signatures to Oxford University School of Biology in central Oxford. OBG called on Oxford University to own what it called “Your Bloody Science” and asked them to “Speak out against badger extermination”, (

There followed a tirade of rather ill-founded and rushed accusations and complaints by multiple members of the usually secretive BTB Partnership (

There followed a tirade of rather ill-founded and rushed accusations and complaints by multiple members of the usually secretive BTB Partnership (

On 24th October APHA’s “Year End Descriptive Epidemiology Reports” for Bovine TB control were published online for the Edge Area counties of Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, Cheshire, Derbyshire, East Sussex, Hampshire, Leicestershire, Northamptonshire, Nottinghamshire, Oxfordshire and Warwickshire. Progress is no longer on target for any of these areas, apparently due to inadequate funding for disease control following Brexit cutbacks (see

On 24th October APHA’s “Year End Descriptive Epidemiology Reports” for Bovine TB control were published online for the Edge Area counties of Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, Cheshire, Derbyshire, East Sussex, Hampshire, Leicestershire, Northamptonshire, Nottinghamshire, Oxfordshire and Warwickshire. Progress is no longer on target for any of these areas, apparently due to inadequate funding for disease control following Brexit cutbacks (see

As the year wound down, the Oxfordshire Badger Group supported a scientific seminar, in Oxford, delivered by Prof. Paul Torgerson on 18th November: key RBCT academics together with Defra & APHA officials were invited to discuss the science and statistics but all declined.

As the year wound down, the Oxfordshire Badger Group supported a scientific seminar, in Oxford, delivered by Prof. Paul Torgerson on 18th November: key RBCT academics together with Defra & APHA officials were invited to discuss the science and statistics but all declined.  On 3rd December, Rob Pownall of Protect The Wild launched a parliamentary petition to end the English badger cull. Standing at around 30,000 signatures at the time of writing, the petition calls for “an immediate end to the cull and the implementation of cattle focused measures to control bTB, rather than what we see as scapegoating wildlife.” As the petition points out, research that has been “peer reviewed and published, shows no evidence that culling badgers reduces confirmed bTB in cattle. Over 230,000 badgers — many healthy — have been killed, disrupting ecosystems without solid scientific justification”. Please add your name to this petition

On 3rd December, Rob Pownall of Protect The Wild launched a parliamentary petition to end the English badger cull. Standing at around 30,000 signatures at the time of writing, the petition calls for “an immediate end to the cull and the implementation of cattle focused measures to control bTB, rather than what we see as scapegoating wildlife.” As the petition points out, research that has been “peer reviewed and published, shows no evidence that culling badgers reduces confirmed bTB in cattle. Over 230,000 badgers — many healthy — have been killed, disrupting ecosystems without solid scientific justification”. Please add your name to this petition