Book Review: A History of Uncertainty – Bovine Tuberculosis in Britain 1850 to the Present, Peter J Atkins, 2016, Winchester University Press

(Link to the online chapters of this book (free subscription required) here.)

By Tom Langton

Back in 2016, having just begun a detailed examination of the Randomised Badger Culling Trial (RBCT) (1), this book escaped my attention. Now with a tatty ex-library copy from ebay, its value and place is clearer. As with the 2019 review by Angela Cassidy (2), it is I believe a substantial contribution to the understanding of the English bovine TB (bTB) epidemic and control policy in the period since ‘badger blame’ emerged in the 1970s.

Peter Atkins, has been a prolific food and drink geographer and historian at Durham University, including inevitably, the disease-related issues. Much of the book is a detailed account of the technical and political context surrounding livestock management and milk production, including pasteurization since 1850, as a threat to human health. This is a compelling blend of what happened and why, regarding the once extremely debilitating and widely lethal bovine TB threat to human health in the UK.

Atkins book was published before the announcement of the 2016 badger cull roll out, which Atkins misjudged as unlikely to happen. Despite this, insight generally seems well evidenced and often convincing, and the book is especially worth reading in terms of what has unfolded since 2016.

Don’t be put off by the cover of the book, that shows nose to nose proximity between a tame badger and a cow, in an unlikely day-time event. This is, according to research done before and since publication, a rare event even at night, which is when badgers are most active above ground. In fact, it is one of a group of photos that has unintentionally proliferated misunderstanding of the transmission of bovine TB from badger to cattle.

Although bovine TB and badgers occupies only the last quarter of the book (chapters 12-15), it manages to get through a good amount of epidemiological practicalities at pace, and provides bouts of eloquent summary. There is a useful collection of around 800 author-indexed references at the back of the book, several of them obscure, with handy library reference numbers too.

Spat between the ISG’s John Bourne and CSA David King

Chapter 12 on epidemiological understanding provides some useful detail on factors such as cattle herd density changes over time, government expenditure on disease control and potential infection pathways. Its thoroughness extends, at least to some extent, to referencing international examples and molecular consideration of spoligotype distribution. Chapter 13 is a rapid road trip from the period where bTB was found in badgers in 1971 in Gloucestershire, through the uncertainties of the badger-cattle disease relationship and infection of badgers by cattle. There is good descriptive summary, albeit with historical account of certain research findings as fact, rather than placed in any measured scientific context of the strength of findings. This is not a criticism as this was not a scientific appraisal.

There is a short history of badger culling from 1971, a rapid summary of the RBCT and the Independent Scientific Group 2007 report and of David King: the government chief scientific advisor’s critique of it. Plus, the spat between the Independent Scientific Groups’s John Bourne and King, that followed. Of some interest is the report that in 2007, it was the Labour government, under Gordon Brown and the MAFF-centric Lord Rooker, that laid the foundations for mass badger culling, even if there followed a delay by Hilary Benn until Labour lost the election to the coalition government in May 2010. There is some basic material on badger cull opposition and the period leading up to the culls starting, but nothing comprehensive. The threats from uncertainty and risk, the focus of the book, are well measured at appropriate points in the narrative. While several of the uncertainties are better understood due to research in recent years, the text for the most part stands the test of time well and is a good general foundation for the student.

Civil Service prone to massive policy mistakes and blundering?

Chapter 14 is likewise an admirable summary for the time of bTB testing protocols, and test accuracy. Examining what is termed the ‘recrudescence’ of the disease in England and Wales since its near eradication in the 1960s, it touches on important disease eradication cost-benefit issues and a more condensed history of disease administration, with even a brief sortie into cattle and badger vaccination.

But perhaps what is most interesting of all, is saved to the final chapter 15: ‘Is uncertainty the future?’. As the writer puts it, ‘what are the lessons the historical geography of bTB has for us?’ There then follows, as a warmup, a look at complexities of some of the spatial questions in bTB epidemiology, raised earlier in Atkins and Robinson (2013) (3) and more recently reinforced by findings from Whole Genome Sequencing. There is an amount of conjecture over ‘scenarios’ that to the historian may seem like useful wondering, but to the scientist perhaps are rather speculative. Maybe a bit of original conjecture is okay, but it stands out a bit in contrast to the bulk of careful documentary.

Then, for me the book turns even more compelling. It addresses the question of why the bTB response has been so sluggish and ineffective, and what is framed as the ‘grotesque cost’ of dealing with diseases of the intensive cattle industry: BSE, Foot and Mouth and bovine TB over the last decades. It looks at the punitive demise of MAFF after Foot and Mouth, and how the British Civil Service seems somehow prone to massive policy mistakes and blunders. Should, asks Atkins, bTB handling by Westminster be added to the ‘hall of infamy’ of policy disasters? But then ‘no’ comes the answer, with a slightly unconvincing defence. His forgiveness is founded on his perception of complexity and uncertainty in the science.

Bang on cue, a sub-section is set up, that chimes with recent discussions over England’s covid-19 early response management entitled ‘A rule of experts?’. The building of policy-lead science (4) to address difficult questions is laid out, leading to the introduction of the concept of dealing with complex and politically tangled issues, framed as ‘wicked’. Based partly on the fact that the problem is dire, unforgiving, labelled as unsolvable and hence apparently justifying unconventional resolution. So ‘Yes Minster’ style consequentialism – where the ‘ends justify the means’: your often ‘tribal’ (5) bad behaviour is excused, and where whatever you decide, you become blameless. Does this government approach sound familiar?

Wickedness unveiled

The last few pages of the book, ‘Bovine TB: a wicked problem?’ may both delight and annoy. They delve into the philosophy of addressing problems that are rated so unbalanced, complex, and frustrated, that the strategy is to manage them, based on continued uncertainty over long periods of time. So bTB is allocated to ‘wicked’ philosophy (6), something that the very senior government officials and scientists may have latched on to at the start of culling as interest in its use began to grow (7). Meaning, that the uncertain outcome of badger culling wasn’t an important issue; it didn’t have to ‘work’ if it induced the livestock industry to accept tougher disease eradication measures that they were resisting. Such approaches are also nicely framed as a ‘clumsy solutions’. All government scientists and vets had to do, whether in the know or not, was roughly comply with a top-down ‘yes, it is the badgers’, undertake a bit of low inference analysis, then maintain ‘you will never actually know directly how much badger culling has contributed to disease control’ and ‘we are going to use every tool in the box’. This of course nullifies a range of professional and ethical pledges, and may be unlawful. But hey, this is a ‘wicked’ problem, these are different times and so anything goes? Those who have said badger culling is criminal may actually have a point?

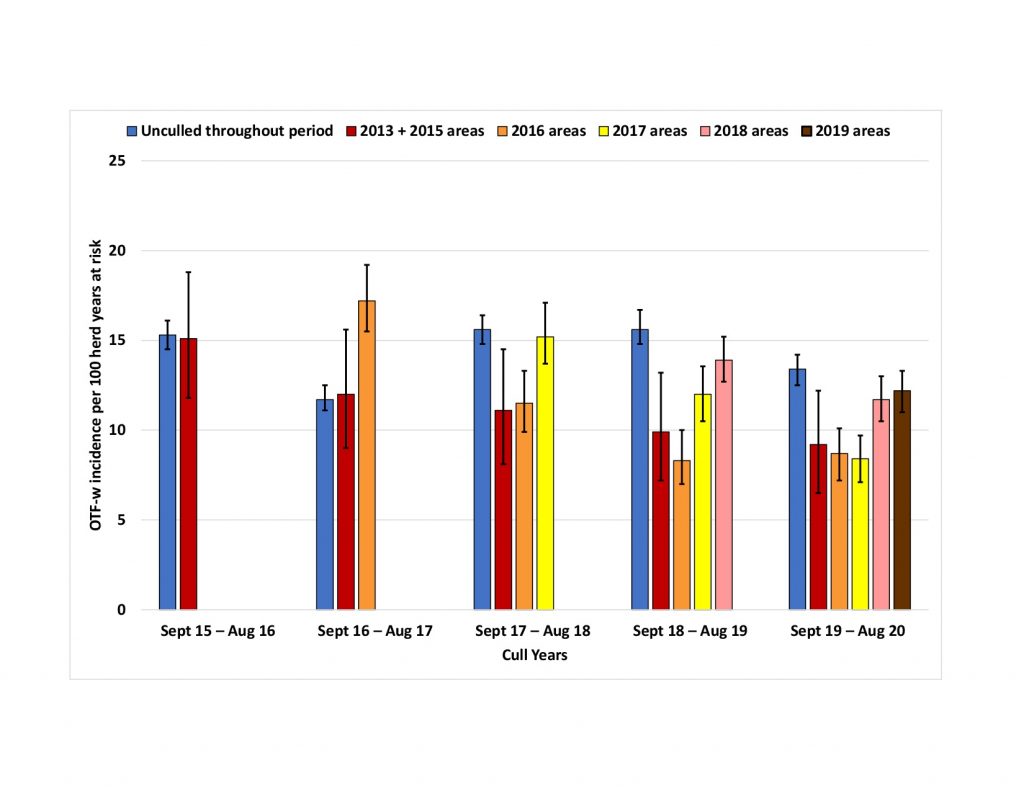

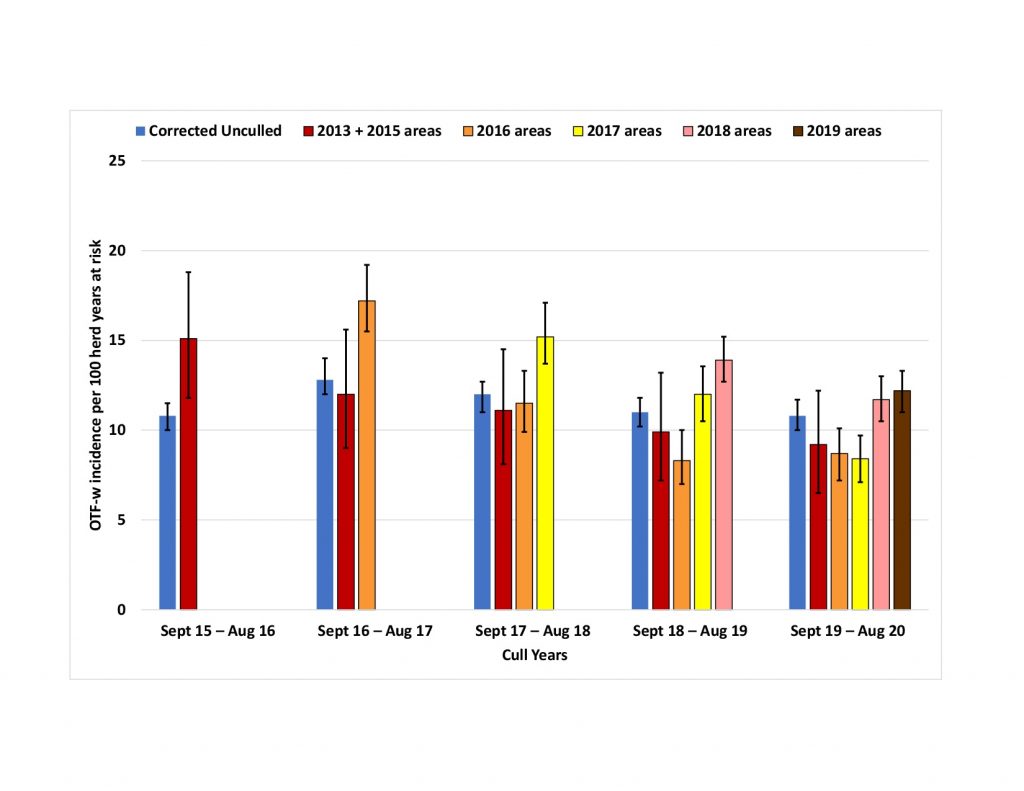

One must ask who was ‘in’ on the badger cull wickedness, who fixed it, made it happen and who drove the car? It is getting easier to see now. Anecdotally, government staff will apparently not deny it in private. This has been clear from multiple sources since Atkins book. But outwardly, in-post, their job comes first and they will follow the tribal line. This helps explain why Defra have reacted so ferociously (and clumsily) to the now emerging data on the badger culls (8) that shows them for what they are; ineffective. The problem must and needs long-term to remain ‘wicked’ for the emperor’s clothes to remain visible. But Environment Secretary Minister George Eustice has lost cull architects Ian Boyd and Nigel Gibbens, and those replacing them may not have been told and thus have greater exposure.

Atkins almost spoils it at the last, as Angela Cassidy did in her book in 2019. He had already come up with his own esoteric home-brew idea that badgers pose more of a risk at certain densities. He points at uncertainty in the epidemiology and the pathogenesis, but not to any deficit in ‘formal sector expertise’, which is a bit over-simplified. He denies ‘selfish individual motives or special interests’ which also looks a tad naïve, given the strength of influence of commerce in the mix. Atkins suggests no one is to blame, or that the blame is evenly spread, which is the diplomatic nice story, but one cannot help feeling that in doing so, like Cassidy he drops into the ‘sticky trap’ of badgers and bTB (9).

Of course, scientific evaluation is not Atkins forte, and there is failure to balance scientific findings according to their limitations. BTB is a scientific problem and you can see as he cites and runs through much of the key relevant literature, that he is not pausing on the uncertainty and hindsight problems within them.

Despite this, Atkins logically foresees the time of effective use of cattle measures that were starting to bite in the High Risk Area as he finished this book, and that they need further tightening with better testing and/or cattle vaccination, to finish the job. Such disease control achievement however, is not the consequence of any ‘wicked’ approach. It is simply what would have happened with strong leadership and without badger culling. And, with all due credit, Atkins also rightly concludes that badgers are likely to be seen as a distraction to the bTB problem when all is said and done in years to come. Again, this book was published before the announcement of the 2016 badger cull roll-out and his last page makes salutary reading, as he was unaware of the mass butchering of largely completely healthy badgers that would immediately follow, and that should hopefully soon be abandoned.

This is a great ending if you are concerned by the repeating car wrecks of government veterinary epidemiology when addressing livestock disease control in England. And how the manipulation of logic and science for expedient high risk approaches, can be endorsed and nurtured in the tribal institutions in public service, given a few wicked people pulling the strings.

A link to the online chapters of this book (free subscription required) is available here.

References

- Bourne J, Donnelly C, Cox D, Gettinby G, Mcinerney J, Morrisson I, et al. Bovine TB: the scientific evidence. A science base for a sustainable policy to control TB in cattle. Final report of the Independent Scientific Group on Cattle TB presented to the Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs the Rt Hon David Miliband MP; 2007.

- Vermin, Victims and Disease. Book review.

- Atkins, P.J. and Robinson, P.A. (2013) ‘Bovine tuberculosis and badgers in Britain : relevance of the past.’, Epidemiology and infection., 141 (Special issue 7). pp. 1437-1444.

- Kao, R. Simulating the impact of badger culling on bovine tuberculosis in cattle. Vet Record 176 February 18 2012. “An underlying problem in this debate is the contrast between the burdens of proof demanded by the scientific and policy constituencies. The burden of scientific proof requires near certainty in outcome; the classic limit for scientific confidence is that 19 times out of 20, a repeated experiment will produce a stated result (ie, the result is within the 95 per cent confidence interval). Policy, however, must balance the efficacy of a potential measure with social, economic and political requirements, and in the event that a decision is to be made, it is made only when the balance of probabilities is in its favour. Thus, there is an inherent paradox in the need to take statistically rigorous, scientifically sophisticated recommendations and view them through the relatively fuzzy lens of sociopolitical realities.”

- Boyd, I. 2021. Scepticism, science and statistics. December 2021 Significance. The Royal Society of Statistics. P 42-45.

- See Pellezzoni I. 2014 Technoscienza 5,2,73-91 and a raft of associated ideas discussed in the Atkins book and elsewhere.

- Badger culling emerged from scientific endorsement but there was no real link between a large experiment with equivocal results and its real-time application. Culling badgers was simply ‘Bourne’s carrot’ using Kao’s (3) acceptance that an arguable balance of probability it might work (see (3) above) was sufficient.

- Thomas E. S. Langton, Mark W. Jones, Iain McGill, 2022. Analysis of the impact of badger culling on bovine tuberculosis in cattle in the high-risk area of England, 2009–2020 Veterinary Record Vol 190 Issue 6. 18 March 2022

- https://thebadgercrowd.org/vermin-victims-and-disease